ONE DAY, ON MY WAY to the metro as I returned home from volunteering, I saw a pale peach leg hovering above the crowd. It floated, disembodied and naked, towards the entrance to Metro Eugenia in Mexico City. I picked up my pace, pushed forward, and made my way towards the ragged man carrying the leg. As I got closer, I saw the lean amputated thigh. The man, sensing my gaze, turned, and pushed the leg towards me.

With a sweep of his hand, he motioned for me to examine a black and blue striped leg warmer. The leg was part of his sales pitch. I rushed past, my eyes locked on the leg, on the suggestion of a body, of dismemberment, of the titillation of flesh, of all the things I saw so often in the news.

And it wasn’t just the leg; I saw body parts everywhere. In front of a rusted brown car in La Merced, the oldest neighborhood in Mexico City, I saw two curvaceous butt and leg mannequins dressed in leopard and zebra pants. On the way to the market, I saw a bra display with twenty busty torsos in various states of disintegration. Often the mannequins were naked, leaving all their tired imperfections on display.

The busts were full of nicks, scratches, and gouges. I walked past a table covered in pale peach arms whose fingers displayed elaborate fake nails, the kind of nails that could stab and kill. Sometimes the mannequins were piled into a truck bed; female torsos tied together and peeling tired silver and green skin. One naked torso sat on the street, full-figured from thigh to breast. Someone had dressed the bust in a black tube top, but they left her bottom naked. A plastic Coca-Cola bottle had been wedged in her crotch.

The visual violence of those body parts reminded me of my first trip to Juárez, one made after two years spent researching violence, after hundreds of days of receiving email and news updates on Juárez death counts. I read about dismembered bodies in the news so much that I half expected to see them, like some vision of the spectral leg I found myself following months later to the metro.

I read of beheadings, gunfights, hands cut off, torsos dismembered, and re-killings (in which gang members chased ambulances holding people that they had tried but failed to kill with the goal of really killing them). I knew that in the winter of 2010 the city averaged 6-7 deaths a day while in the summer the numbers rose to 11-12. I traveled there in May and imagined that the execution meter fell somewhere in between those statistics.

When I arrived at my hotel, I was ushered into a vaulted, air-conditioned lobby. The man at the front desk asked me, with a twinkle in his eye, “Are you here for business or pleasure?” I didn’t know how to respond. “Who visits the most dangerous city in the world for a vacation?” I wanted to shout. Everyone in the hotel lobby was in a suit, presentable, cool and collected. Meanwhile, I wore cut-off shorts and a Goodwill t-shirt with Chinese writing.

I felt safer wearing a shirt with language that no one, not even myself, could decipher. While standing at the front desk, I looked outside at a giant turquoise pool surrounded by palm trees. The temperature outside topped 100 degrees, but even that was not hot enough to tempt me to get into a bathing suit in the most dangerous city in the world.

Julián Cardona, a photographer from Juárez, met me at my hotel and rode a bus with me to the city center. I had interviewed him a year earlier, and he told me, “If you ever come to the city, let me know.” For our first interview, he had crossed over from Juárez to El Paso to meet me at a Starbucks. He had no reason to help me, an unknown graduate student, with my research. And yet he did.

Like any good photographer, he was an everyman, and could blend into any crowd in his worn jeans and t-shirt. He was an observer, and in order to do that, he had to become a part of his environment. From our hour-long interview, I gathered that he was a man of few words, but of definite action. He would meet a young graduate student attempting her own small written revolution against violence at the airport in Juárez if she should come visit. And a year later, without so much as a question, he did.

Other people wanted to know what I was doing and why. They wondered why I was interested in Juárez. When I crossed the Canadian border to go to a conference on Latin American Studies in Toronto, the border guard said, “Why don’t you study problems in your own city?” This sentiment was common. People wanted to know why I cared about Juárez. Studying and writing about violence was often depressing. What kept me going was learning about families and activists who were transformed by the violence. They did not remain victims but passed through that stage and found the strength to fight against corrupt institutions.

My first day in Juárez, Julián and I walked to La Mariscal, the red light district that had been demolished some months earlier. The prostitutes and drug addicts had been forced to move to other areas of the city. I walked the streets timidly but curious to see the geography that I had written about.

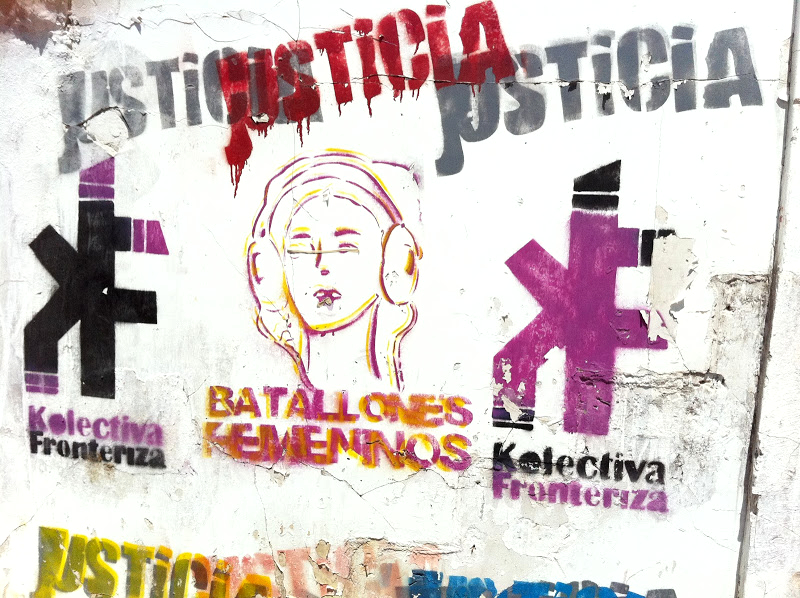

“Don’t take photos on this street,” Julián warned me. I walked past telephone poles covered in flyers with the faces of missing girls. I was busy inspecting anti-government graffiti and demolished buildings when he asked, “Do you drink?”

I almost said yes, but then I remembered where I was and said, “No. Well, sometimes. Yes, sometimes, but not here.”

He pointed to the Kentucky Club, and said, “They invented the margarita.”

“They did?”

The Kentucky Club, one of the oldest bars in the city, was a vision of dark polished wood. It was deserted. No one was drinking at midday except us. The bartender lamented the decline of the city.

As evening approached, Julián took me to one of the last safe public spaces in the city, an oasis for intellectuals, writers, photographers, and academics: Starbucks. It felt strange to order a latte, to be sitting calmly in Starbucks surrounded by iPads. A friend of Julián’s arrived, and told the story of his recent carjacking. He was in his car at a stop sign, and he waited for a young guy to cross the street. However, the guy pulled out a gun, forced him from his car, and drove off. At that very moment, a police car passed by, and Julián’s friend jumped in. They began to chase his stolen vehicle.

“Where did your car get stolen?” I asked.

He pointed out the window of Starbucks, and said, “At that stop sign.” Violence remained at a distance, a story told, a finger pointed.

Over the next few days, I drove through the militarized streets past lines of black trucks packed with men armed carrying AK-47s. Sometimes policemen drove by on shiny motorcycles that looked as if they had been polished by hand.

When I visited the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez to meet with students, they told me that life was both normal and surreal. A girl with blue hair said, “When my family goes on vacation to Acapulco, people ask where I am from. When I say Juárez, they immediately whisper, ‘Are you fleeing?’ And I reply, ‘No, I’m on vacation.’”