So, not all that long ago, we raged a little on the silly things people do when they put huge effort into helping others, but couldn’t be bothered to pick up a history textbook, or pause to consider the implications of their interventions. Free shoes, painting cluster bombs like food parcels — such hilarity as you hope would never be repeated a year or so down the line. Or ever, really.

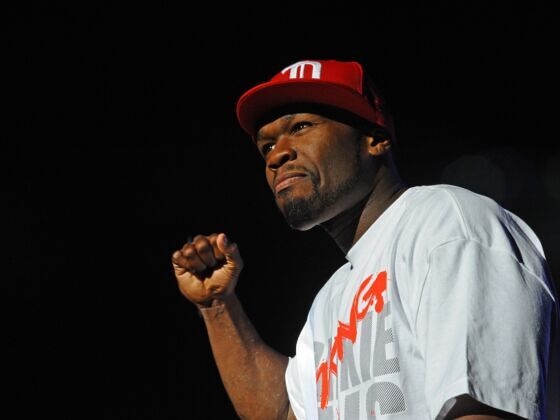

Some folk, like 50 Cent, who we criticised for essentially holding starving kids ransom for Facebook likes, is probably pretty unrepentant. But upstanding citizens, like the US military for example, no longer feed children in faraway lands cluster bombs for dinner. Well, by accident.

You’d expect, then, that real international aid organisations — as opposed to rappers or soldiers — would be the first to avoid repeating the most obviously reprehensible sins of their forebears. But a recent ad partnership from the World Food Program, of all entities, suggests that while they’ve been learning from 50 Cent’s program of feeding the starving when you like his Facebook page, they’ve mostly been taking how-to notes, instead of maybe-this-is-ethically-horrible notes.

For those who never read about the 50 Cent fracas (you really should, its riotously funny, except for the gross exploitation of the starving), it went a little something like this:

- Find a bunch of starving people.

- Put a budget aside to feed them.

- Pledge to spend that money paying for meals for said people only in exchange for Facebook likes.

- Become popular on the internet off the hunger of the starving.

(I made #4 up. It’s probably not in the powerpoint that the guys from marketing presented.)

So why was that a Bad Thing™ again?

Well, in the simplest analysis, it’s pretty close (cough…incredibly close) to extortion, in that it relies on a logic that says, “I have the money to spend on these starving people, some of whom may likely die or suffer if it is not spent on them. In fact, this money is actually earmarked for spending on them. Like, I could cut a check right now if I wanted to. But I won’t unless you like my product on Facebook.” In 50’s case, this was an energy drink.

That smells a lot like holding the lives of the starving hostage and demanding marketing exposure for their lives.

Approached with slightly more analytical nuance, it’s putting a price on the head of the starving in a place like the Somalia of 2011-12. At its core, there is a basic offer of exchange between a meal for a starving person and a Facebook like, and the implication that but for being given something in return (fractionally tiny promotional exposure), this person is simply not worth saving. As in, we have the money to feed them, but feel no compulsion to spend it on food except where paying it will also give us a presence on your Facebook feed somewhere. Gone, completely, is any notion that this person should be helped simply because they are hungry, in pain, or human. Where to do so is simply an ethical obligation. In fact, it is precisely this person’s pain and hunger that we are attempting to exchange with you, the customer, in return for your Facebook like.

Conceived more succinctly, such a campaign works to establish the (revolting) idea that relief from the pain of others is a thing that companies can now sell you. It’s a market in which the hunger of the starving Somali (and any guilt you might feel towards not helping them) can be exchanged for a Facebook like. Even more perversely, while a company somewhere can now realise tradeable value off packaging and exchanging the pain or hunger of some unknown third-worlder, that starving person him/herself has no access to, power over, or share in that exchange. They (or more accurately, their suffering) becomes a source of marketing and potential revenue for more powerful organisations.

Shifting ideas of our responsibility to help the suffering from being an absolute moral obligation to a tradeable commodity feels like a very, very disturbing thing to be wanting to do.

Yeah. That’s revolting. But as long as the idea doesn’t gain any traction…

Except that now the World Food Program appears to have participated in exactly the same kind of commodification. The world’s heftiest posterboy for feeding starving people in faraway places, via their partner DSM (a science and innovation organisation), now appears to have promoted exactly the same kind of relief-for-likes thinking via this ad campaign.

The more likes the WFP got on their Facebook page, the more meals DSM would donate for the feeding of some unknown, but valuable commodity — I mean, human being — somewhere in the world.

But…it’s the World Food Program!

Which is what makes it so disturbing. If it’s exploitation when 50 Cent does it, and we think starving people should be assisted as a moral duty, rather than as a consequence of having their pain sold for advertising, then why should it be any less unacceptable when this hunger-for-exposure mechanic gets rolled out by the WFP? Does it make a moral difference to what is being done (the commodification of hunger, and erosion of a moral imperative to help the suffering of others), when it’s being done by a popular aid agency rather than a popular rapper?

The claim on WFP’s part seems to be that raising their profile on Facebook means they’ll be able to get more help in their mission of feeding the hungry (by, ironically, the implicit threat of not feeding them if you don’t give up your like). But is that potential gain in exposure for WFP’s activities enough to excuse the effect that a hunger-for-exposure market has on modifying how people think about their duty to help? And surely 50 Cent could also claim he was ‘raising awareness’ of the famine in Somalia at the time.

Something feels pretty uncomfortable here.