A FERN OF SCARS grows across her face. Her voice is weak. It makes the kind of noise you hear after waking from a dream — the soft trespass of a ghost or thief.

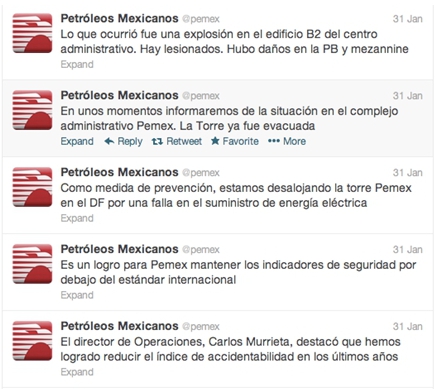

Mexico’s President, Enrique Peña Nieto, tiptoed around many soft-spoken victims in the hospital after a January 31 explosion at Pemex headquarters in Mexico City killed 33 people and injured 121 more. Pemex is the country’s national oil company, created in 1931 when Mexico nationalized the oil industry.