“Nooooo!” screamed the sheep. A terrible ovine shriek that combined raw fear with retaliatory death threats to friends and immediate family. Now what kind of behaviour, I wondered as my heart attempted to pound its way out of my mouth, is de rigeur when confronted with a shrieking ovine?

My first instinct was to drop my camera — the item that had prompted the bizarre incident in the first place — and hotfoot it somewhere less supernatural. But wait. This was ridiculous. Do sheep really scream like women? Had it really opened its mouth, moved its lips? Do sheep even have lips? I re-examined the scene.

The sheep stood nervously (and not a little awkwardly) in the doorway. It was surrounded by a halo of steam, its wool shaved off in seemingly random patches. It looked absurd, even by sheep standards. Something in the darkness moved, a hunched, veiled figure at the back of the room – a woman. She yelled again, loud and venomous, the Arabic equivalent of “get the fuck outta here now”. The sheep and I jumped in tandem. I apologised vaguely to the animal and the darkness and continued my route through Sidi Ifni’s powdery medina.

I’ve done it again, I thought. Been shouted at for trying to shoot a Moroccan woman. With a camera, sure, but save for bullets what’s the difference, really, between a camera and a gun? We point, we focus, we shoot, we reload (batteries). Anyone with a camera, professional or amateur, that marauds the earth in search of exotic subjects to “capture” cannot fail to notice a certain hunter/prey dynamic.

Cameras instil fear into people. They can hurt. I know this because I’m a travel photographer and over the years I’ve been heckled and shooed away many times, especially in countries like Morocco. I’ve had exotic curses rained upon my sick soul. Hirsute, sweating men have raised meat cleavers and furious women have brandished sticks. I’ve made young children dive into bushes by zooming past in cars and taking ‘pot-shots’ (more gun terminology, there) while leaning out the window like a macho stunt maniac.

All contemptible behaviour of course and definitely not something I’m proud of. Oftentimes these situations come about unintentionally. Most photographers know the feeling of raising their camera to shoot something ‘innocent’ (a colourful wall, an empty, attractive street – a sheep enjoying a sauna) and suddenly being yelled at by someone they didn’t see. But this wouldn’t be a confession if I didn’t admit that I have taken plenty of photos in situations where I knew there was a chance of offending someone or pissing them off.

I took this shot spontaneously while walking by. Seconds later a man from a nearby kiosk was shouting at me angrily, even though the people I was photographing didn't seem to care at all.

Not because I’m an asshole. If I thought I’d end up wielding my camera like a gun, I would never have become a photographer in the first place (I’m honestly not that type of guy)…but because I’m human. I realize that sounds like a pathetic fig leaf to cover an embarrassing lack of ethics. But it’s not. I do have an ethical code, one that has naturally accreted and solidified over more than a decade of travelling and taking photos of people. In fact as a professional, I’m probably more aware than most of the moral challenges involved. I know about asking permission. I know about talking to people, explaining why I want to take a photo, about model releases and trading gifts for images instead of money.

When I asked this man for a portrait, he was okay but rubbed his fingers together in the universal sign for money. I paid him what I had in change, the equivalent of two dollars. I did not believe this would have a negative effect on tourism in the remote mountain area I was in. Conversely, now that I am using the shot, I wish I had paid him more.

But it’s not that easy. In fact it’s way more complex. In the same way we all break society’s rules in small ways, we sometimes break the laws of photography too. There are deliberate transgressions – shoving a camera in the face of someone that obviously doesn’t like it is the equivalent of getting all up in someone’s grill in a bar or on the street. You deserve whatever consequences come your way.

But there are less straightforward situations, the equivalent of not buying a ticket for the last train home because you’re running late. How do you know in an instant whether a stranger is saying they don’t want to be photographed because they’re shy, sceptical or it’s against their religion or beliefs? How can you ask someone to sign a model release form if they’re illiterate or don’t speak your language? How can you know in advance whether your photograph will be sold to a magazine, used free of charge to help a charitable cause or be used purely as a personal memory?

Is it so bad to give someone in extreme poverty a couple of bucks for taking their photo, especially if you know you would have given them money regardless of the photo? Will it really set such a terrible precedent for future travellers? Is giving useless gifts any better? How do you convincingly explain in a language you don’t speak that it’s not their face you were drawn to but someone’s colourful kaftan or pointy-hooded djellabah?

I don't like photographing women too much out of respect, but what to do when colours like this pass you by? I don't feel I have been culturally insensitive since their faces are not shown.

Mostly, you can’t. As with everyday life, you have to go on intuition, live in the moment, weigh up situations and scenes as they occur. That’s what makes the job of a travel photographer simultaneously exciting and ethically suspect. A photographer in a country as anti-Camera yet intensely photogenic as Morocco is a reformed gambler in a casino with a pocket full of tokens surrounded by flashing machines. Sooner or later, he or she is bound to give into temptation.

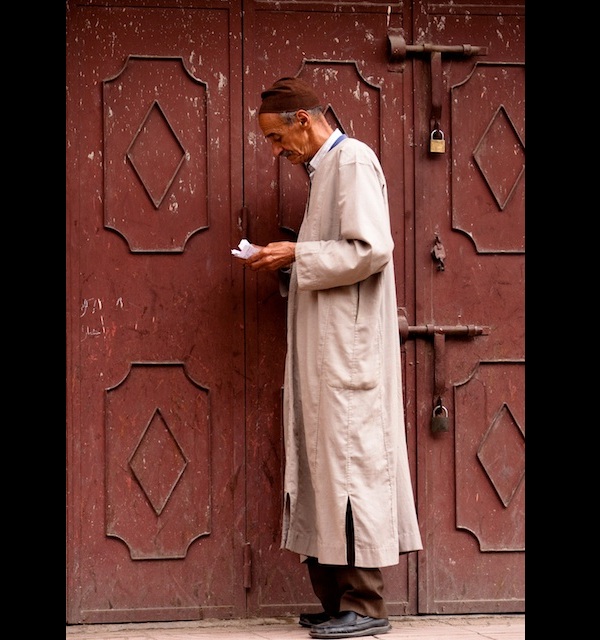

I did not intend to invade this man's privacy, though if he had noticed me he may have thought I did. I was just momentarily drawn to his concentrated expression, the vertical lines of the scene and the harmonious colours. How to explain that in Arabic?

The truth is, having a completely rigid moral code sometimes just doesn’t work for a professional travel photographer. The reality is that you’ve spent time, effort and likely a large portion of your budget (if you’re lucky enough to have one) coming to a foreign land specifically to take photos. You cannot – and don’t want – to leave without shots of the inhabitants of that country. (How on earth are you going to get into the pages of National Geographic otherwise?). Anyone that says they haven’t bent the rules to get a killer shot is lying.

This dude was happy to have a shot taken of the fish he was about to cook us. Knowing we were tourists, he afterwards charged us over 70 euros, more than any other meal we'd eaten in any of the hotels we stayed at, taking advantage of the fact we had forgotten to ask the price in advance (thinking it would be cheap). We shouldn't forget that other cultures sometimes lack ethical codes also.

But precisely because we do bend the rules at times, it’s even more important to know when we shouldn’t. We need to know when to resist, when to put the camera away and quit with the persuading and payments and protracted dialogue. We definitely need to be aware of when a situation is slipping into individual or cultural abuse. We need to be especially sensitive towards women and children. If someone seems genuinely upset we should delete their photograph in front of them. When we get to the point, as I have now and again, where the people around begin to exist only as elements in a composition, we need to pause and re-engage.

If being human is a legitimate excuse for taking occasional liberties, it’s also an equally good reason to not step out of line. These are fellow human beings we’re raising our visual weapons at, after all. As Gandhi said, an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind. Cameras should be a way of making everyone see, not making everyone see red.