TWO YEARS AGO, I came across a story by Tao Lin in VICE entitled Relationship Story. Although I’d been following and enjoying Tao’s writing for several years, this new work felt like a leap in his progression, almost like a surfer who’d switched to a different board and could now reach new places on a wave.

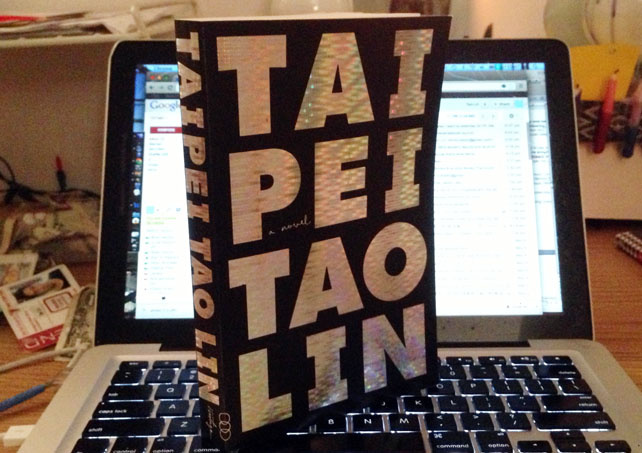

Published last month by Vintage, Taipei, Tao Lin’s 7th book, is essentially the continuation of this story, and the first book I’d recommend to people who want to read a next-level novel, something akin to space-age journalism.