Chi Kung Health Balls. Photo by Chandan Singh

**Nb. If you missed Part 1, start here.

Friday, June 18, 10:45 AM: Clubhouse Ballroom, Stanford University

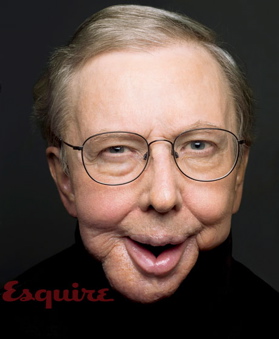

I RECOGNIZE HIM FROM THE THUMBNAIL photo he runs every month alongside his Letter from the Editor. In it, his hands are featured as prominently as his well-lit cranium. He gestures as if juggling a pair of Bocce balls, joking with an off-camera associate about — I imagine — the extraordinary heft of his, or someone else’s, cojones.