Shipwrecks may be bad news for sailors, but they’re great news for travelers who love seeing abandoned places, historical sites, or places just considered especially unique.

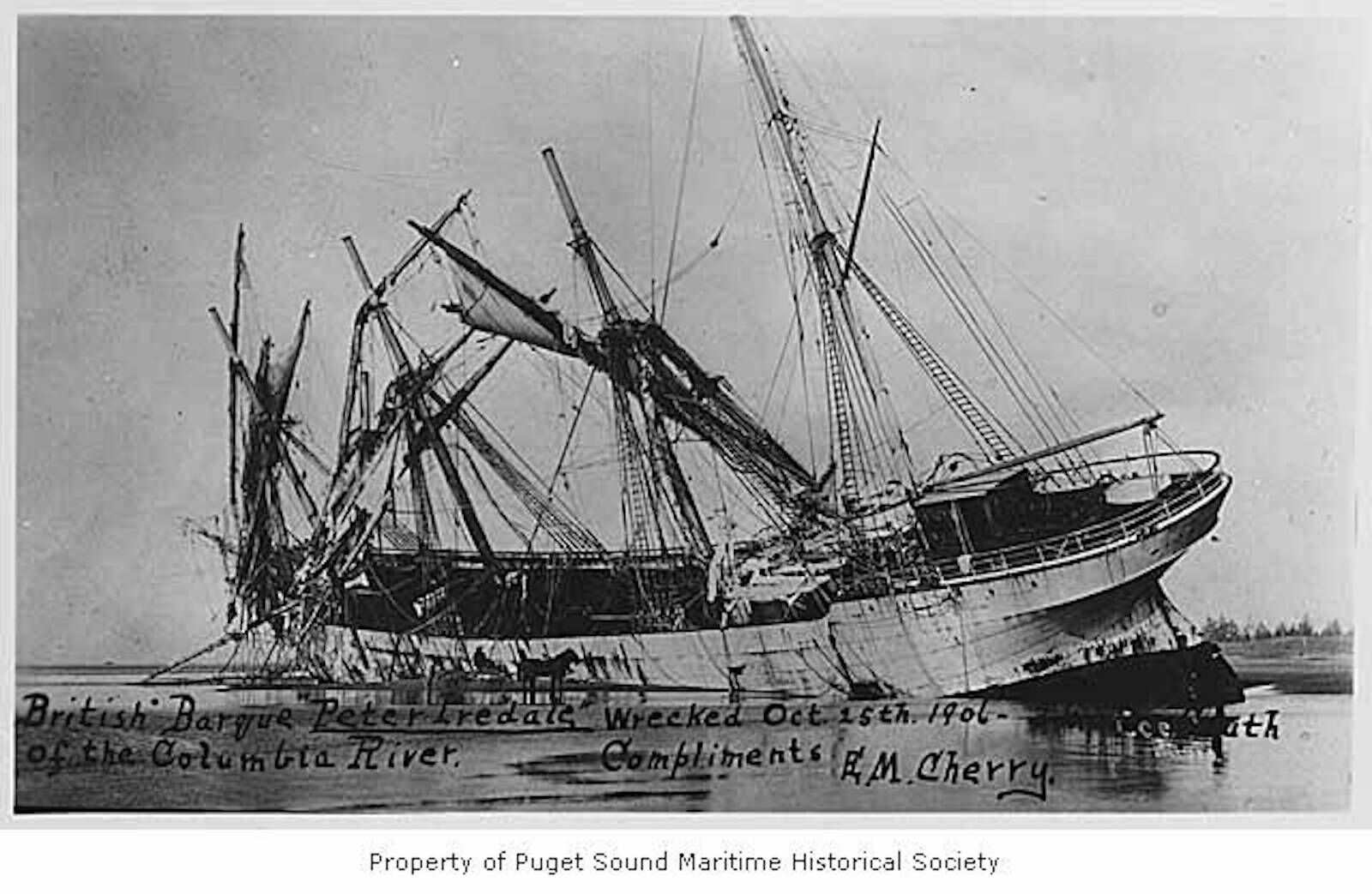

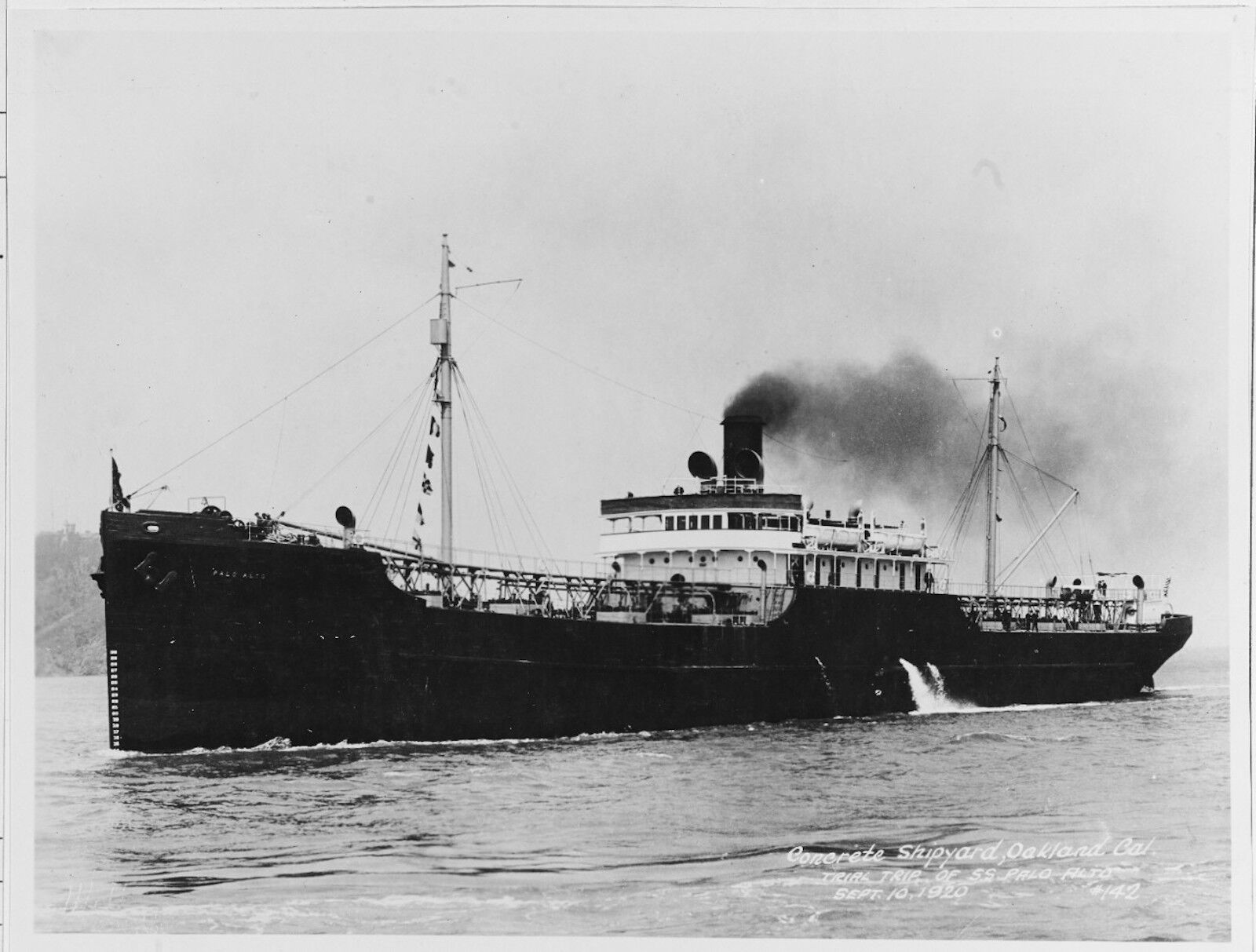

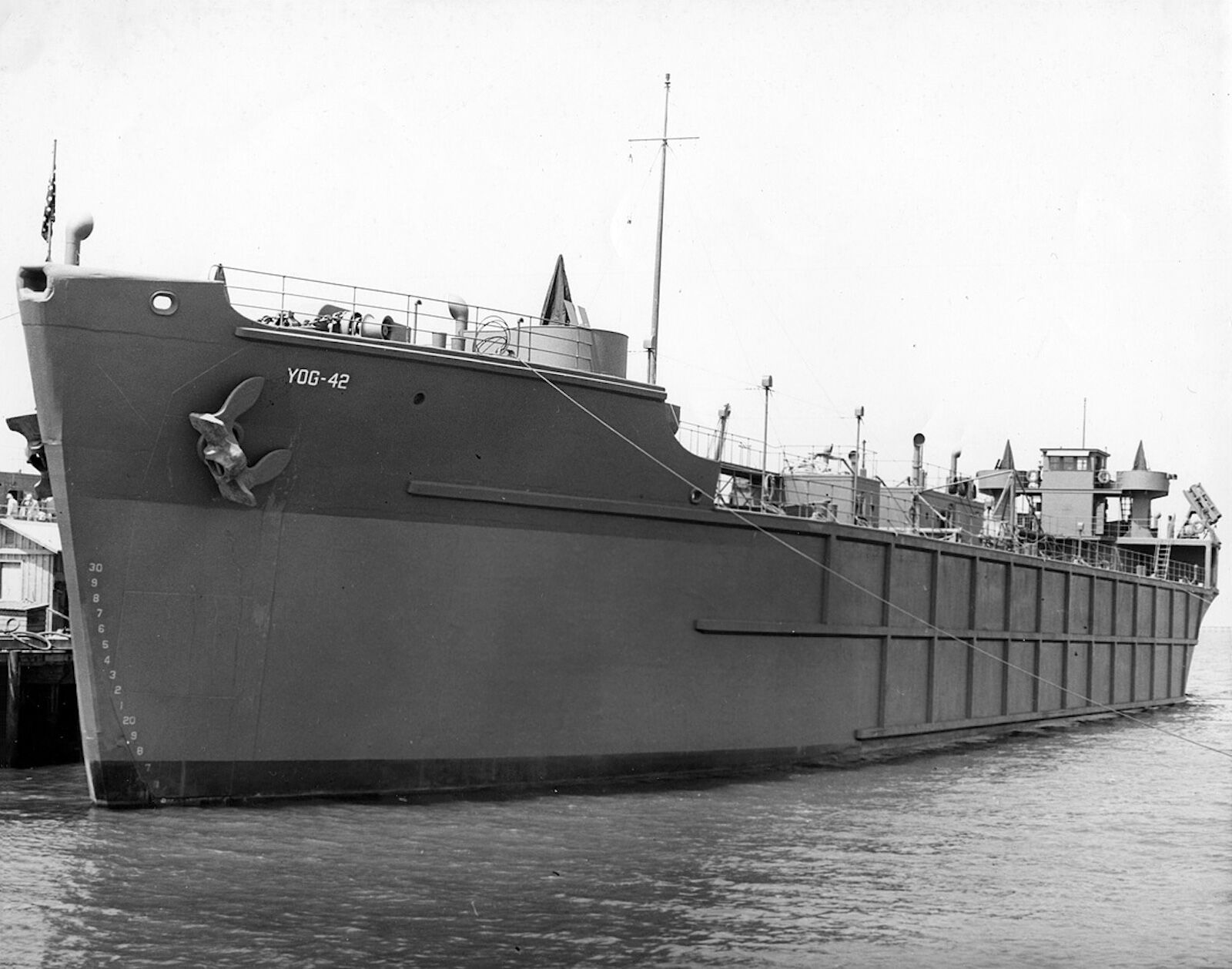

The western coast of the United States has brought down its fair share of ships, either from poor weather, unmarked reefs, or shorelines that gained elevation just a little too quickly for older ships to avoid. On top of that, many of the best shipwrecks on the West Coast were internationally sunk (after being cleaned, of course) to create reefs for marine life.