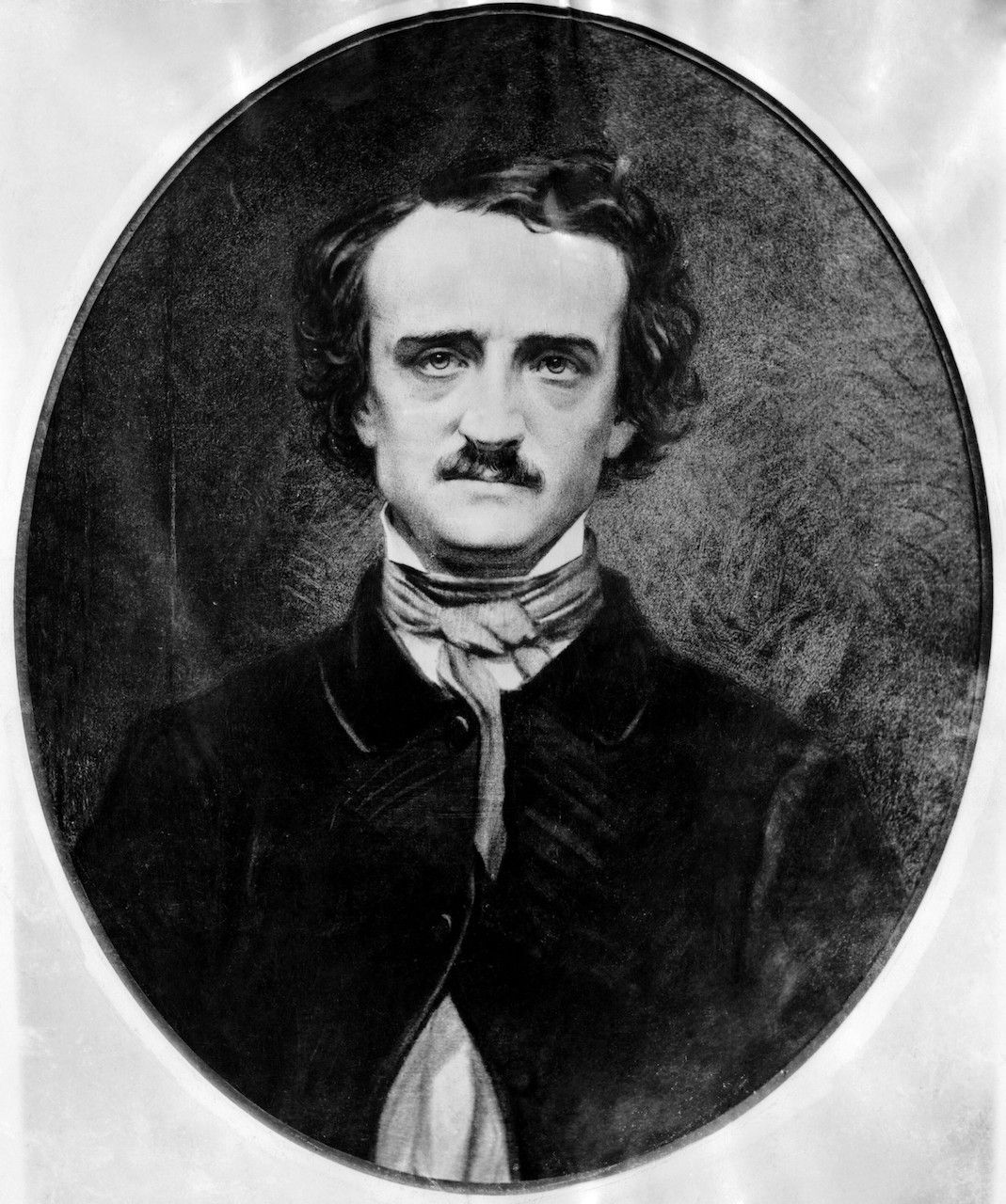

On a recent trip to the Isle of Palms, it took less than a day to learn that one of America’s original horror writers, Edgar Allan Poe, is a source of obsession in this small corner of South Carolina. The Uber driver taking me from my hotel 20 minutes southwest to nearby Sullivan’s Island my first day there took it upon himself to educate me.

“Did you know Edgar Allen Poe lived on Sullivan’s Island?” He asked. I did not know. “He joined the military under a pseudonym.”