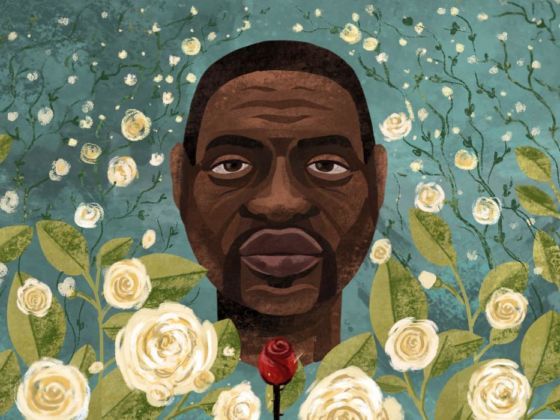

Dear Gianna,

Millions of people know your name now, and like most of us I first found out who you were a few days after your father’s murder. In that time between, the people of the United States erupted on your dad’s behalf. Even though we are still braving a global pandemic, Americans flooded the streets with their cries promising no peace without justice, proving that they would not tolerate your father’s death at the hands of the state under literally any circumstances.