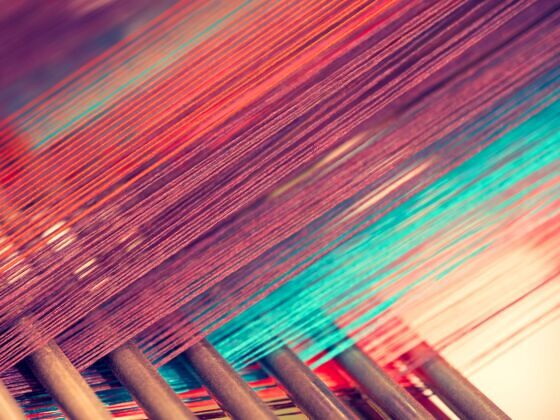

IN JERUSALEM, I lived in a room with a loom used by the woman of the house to weave garments for the Temple priests. A room that smelled to me of time travel. But to the weaver, the garments, the priests, and the Temple were all objects of the eternal, meaning they were not objects at all. They were thoughts in the mind of God, written down precisely, and in luminous detail, in Leviticus.

“I am part of a group dedicated to rebuilding the Temple,” she said matter-of-factly. She could as easily have been saying, “I am part of a book club.”

I didn’t know what to say. As a friend of a friend of her husband, I was given the room for free. I never actually saw the priests’ garments she wove. I never asked to see them.

“To rebuild the Temple, you will have to raze the Dome of The Rock and Al Aksa,” I wanted to warn her. Our sunlit room in Katamon would have burst into holy war, an old-fashioned Biblical brawl with bile and burning camels. By destroying the second Temple, the Romans made it indestructible in the Jewish psyche.

Jewish prayers lamented it; pilgrims journeyed to Jerusalem to weep for it; couples still smash glasses underfoot at their weddings to remember it; Orthodox Jews wait for the Messiah to come and rebuild it. Jews like the weaver, emboldened by Israel’s re-conquest of Jerusalem’s Old City after the Six Day War in 1967, decided to take matters into their own hands.

In a way, they are like travelers at a station who have been waiting two thousand years for their train. The day came when they could wait no longer. They would build their own train.

In the West, a Temple fixation is hard to imagine. Maybe the closest you would come is the image of a mass of people sleeping outside a computer store for seven days and seven nights to purchase the latest software gadgetry. Maybe.

Every day, I would return home from interviewing Palestinians to this place where holiness was being cooked on a loom. On the floor, there were always new scraps of thread I hadn’t seen before. Exiles like myself. Sparks that didn’t quite make it into flame.

I’d be sitting there reading Joseph Goldstein, Jewish Buddhist, with his tame reminders about following the breath, returning home to the heart. We were like two mice at the foot of something enormous, mountainous, only flat. In the next room I’d hear her breaking open an orange with her impatient thumbs.