Photo by Zweettooth

The desire to travel can be spurred by a variety of motivations. To see the world. To push our boundaries.

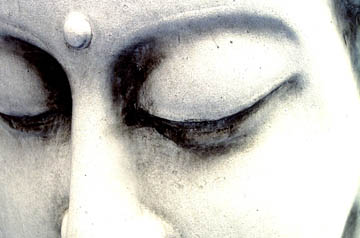

Perhaps to gain the ultimate truth: enlightenment.

But what is enlightenment? And how would we know it if we found it? For me, I’ve found a valuable guide in Zen Buddhism.