Bruno took another sip of beer as we watched the sun set over Rio from the summit of Two Brothers Hill.

“I used to be happy we had this view to ourselves,” he said, as he looked down at the wealthy districts of Leblon and Ipanema. “But it’s so beautiful, I want to share it with the world.”

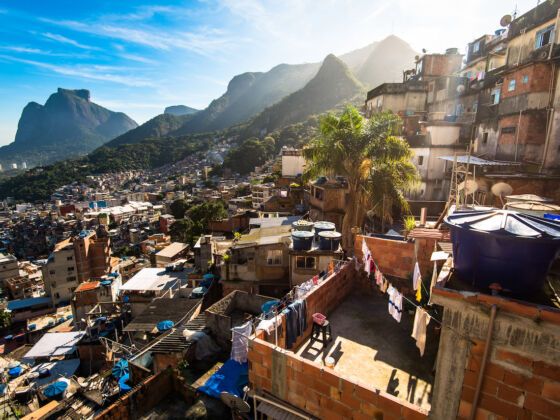

Unlike its more famous neighbours, Corcovado and Sugarloaf, the only way to reach the top of Morro Dois Irmãos is by going through Vidigal, one of the hundreds of favelas that dot the skyline of the Cidade Maravilhosa. Long derided as brutal dens of violent crime, drug dealing and murder, favelas are largely avoided both by tourists and middle-class Brazilians. But like everything in this fascinating land, the reality is more complex. I had come to teach at a community centre in the neighbourhood to find out the truth for myself.