Serve hot, drink frequently.

I AM STUDYING at a small college for Tibetan refugees outside of Dharamsala, in the foothills of the Indian Himalayas.

Our days are arranged by tea breaks.

Serve hot, drink frequently.

I AM STUDYING at a small college for Tibetan refugees outside of Dharamsala, in the foothills of the Indian Himalayas.

Our days are arranged by tea breaks.

At dawn, I wake to the sound of Tibetan chanting drifting from the temple, but don’t get out of bed until my roommate Bhutti comes in after prayers and urges, “Emy, you want tea?”.

The school’s chai, Hindi for tea (cha to Tibetans), is milky white and very sweet. When the bell rings at 10:00, monastic and lay students pour out of their classes and join the line. The Tibetan students eat quickly without talking, then hurry to the little shack behind the girl’s dormitory, where the chai is darker in color and served in small glass cups.

The Americans learn to eat quickly and join our friends and roommates for chai and spicy snacks before afternoon classes. During evening study break, students again gather for tea in the little store on campus that sells basic necessities like chips and pens and soap. The shop owner dances to Daddy Yankee’s “Gasolina” while passing out little espresso sized mugs.

Though tea breaks are now deeply ingrained in the daily Indian rhythm, tea has only been popular in India since British companies ran aggressive marketing campaigns in the early 20th century; elegant demonstrations of tea preparations were performed in high-class houses, and tea breaks were built into the working day at factories and tea plantations.

Heat the water with crushed fresh ginger and cardamom pods before adding the tea.

Susanna Donato

Rita uses the flat edge of a knife to break open a hunk of ginger root and crush a couple of cardamom pods. She tosses them into the pot, and I watch as the ginger releases its juice into the swirling currents. The steam clears my sinuses and makes my eyes water. The fresh cutting ginger scent is tempered by a soft undercurrent of cardamom, like Christmas in Sweden. When tiny bubbles begin to rise from the bottom of the pot, Rita drops in a couple of black tea bags.

As soon as black tea reached the streets of India, chai wallahs began concocting their own brews by mixing in spices such as cardamom, cinnamon, ginger, and peppercorns, built on ancient Ayurvedic traditions of preparing spiced, milky drinks for medicinal purposes. British tea merchants were miffed at this development—with the addition of spices and lots of sugar, Indians needed to use less tea to create a strong flavor.

Rita is a nanny for an American family in Brussels. Every morning before I go out to explore the city, Rita and I make chai, and she tells me the gossip about the neighbors.

She uses British tea bags, reduced fat milk, and no sugar.

Buy Assam Tea, CTC .

In the weeks after returning from India, I feel deflated and adrift, puzzled by the most basic habits of living, and unable to express exactly what I am missing. I set about trying to make chai. I use Lipton first, but the flavor is too light. In an Indian grocery store in Atlanta, I find Assam tea that comes in a bulk bag of tiny black pellets. When the bag breaks, the pellets spill all over my cabinet, looking like mouse droppings.

I do not measure, just pour a couple of spoonfuls into the boiling water. The tightly rolled leaves color the water almost instantly, a deep, almost orangey brown. The aroma is like crushed grass.

The development of CTC (Crush, Tear, Curl), a mechanized process that creates strong flavored and very inexpensive tea, solidified tea’s popularity in India in the 1960s. Chai serves as a sort of uniter in a country of vast divisions in wealth; it tastes basically the same at street stalls and in gated homes.

You cannot make chai sweet enough.

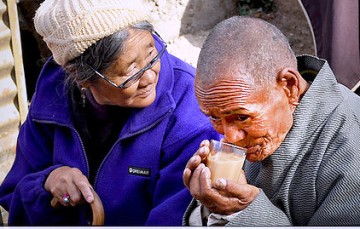

We wrap wool shawls about our shoulders and clutch our chai glasses against the chill morning air. A crew has gathered—men in shirts that hang off their bodies, chubby women in bright salwar kameez, an old farmer with a goat–as we watch for the bus to arrive on the street corner. The dust in the air is lit golden by the low sun. As I sip the tea, strong and syrupy sweet, I shake off my morning blur. Bhutti reaches for the little metal sugar bowl, and adds two more spoons of sugar to her tiny cup.

“It’s not sweet enough?” I ask, amazed. Bhutti laughs.

“Isn’t the bus supposed to come at 7:30?” Lara, my American classmate, asks, nervously glancing at her watch. It is now 7:35. Ani Kelsang, a Buddhist nun, shrugs and orders us more tea.

All that day, I can taste the sugar on my teeth, as the bus bounces higher through the hills, past tea plantations and yellow mustard fields. I am grateful when we check into our room at the monastery guesthouse to finally brush my teeth.

Use whole milk.

Even after I’ve bought Assam CTC, my attempts at chai turn out watery and bland. I become increasingly frustrated. If only I could share this drink with my friends and family, I think, I wouldn’t have to explain about the grimy turquoise roadside teashops, the glass cups barely bigger than a double shot glass, the unhurried pace of life mirrored by the cows ambling by…We’d sip together the accumulation of tastes and memories.

The thought of cows brings the answer to me with a start. The milk used by the little teashops was often fresh from local farms, or at least packaged with all of its fat intact. The idea of removing fat from milk is laughable in a country where many struggle to get the right nutrition. I put aside the skim milk.

Boil all the ingredients together until the milk froths and nearly boils over.

“No Emy,” Bhutti curls her fingers around my wrist to stop me from turning the stove off, “you must wait, or no tasty.” I draw back, chastened. This is the first time Bhutti has entrusted me with any household task while staying with her family, and I am eager to do right.

We are in Bhutti’s tiny village nestled between harsh peaks in the remote Indian Himalayan region of Ladakh. I spend my days breathing the crystal clear air and wandering through miraculously green barley and pea fields, while Bhutti and her family plow, irrigate, cook, clean, and tend the goats and yaks.

Bhutti has me wait until the milk puffs up to a centimeter from the rim of the pot. Then, with expert timing, she turns off the stove and the froth collapses in on itself. The next day, she will let me make the tea unsupervised.

Tea first, then working.

We are gathered in Leh, the capital of Ladakh. The Americans reach for knives, eager to begin the long process of making momos. There are piles of cabbage, carrots, onions, potatoes, to be chopped into tiny pieces, dough to be mixed and kneaded. We have told the driver to come back in two hours, and are nervous about having enough time. But our hostess waves away our hands and gestures for us to sit on the mats on the floor. “Tea first,” Wangmo insists, “then working.”

We finish eating momos nearly three hours later. Someone brings a plate out to the cab driver. He grumbles about the wait, but does not leave.

Back in the US, I finally achieve a chai with the right balance of tea and milk, sweet and spice. I serve it to my housemates. We sip it in the living room on a cold winter afternoon, our laptops open and papers spread around us.

What daily ceremonies do you arrange your days around?