There is nothing more soulless than a banking town.

The term alone conjures images of imposing glass towers full of boring people who care about nothing but money and how to make more of it. In America’s second-largest banking center, it’s an image that’s been tough to shake.

It’s not a bad image, necessarily. Charlotte never had a river catch on fire or a string of federally indicted mayors. But to many, Charlotte is landlocked and nondescript, a city built on banking that’s got about as much character as a credit card bill. Ask anyone what they think about Charlotte, and they’ll typically shrug and mutter something about rocking chairs at the airport.

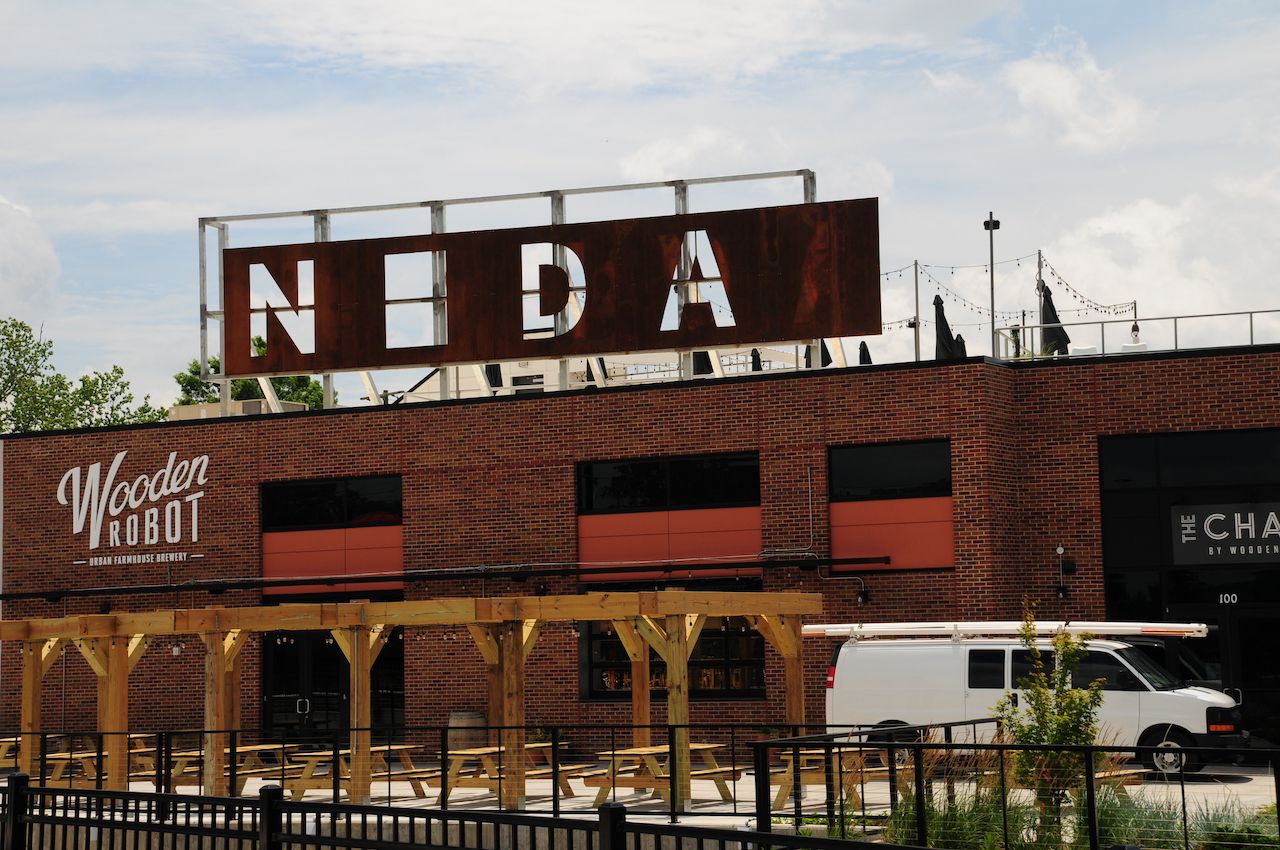

But in 2019, a sea of transplants and finance-weary locals are finding the beauty in this city and crafting a culture in the shadow of glass towers.