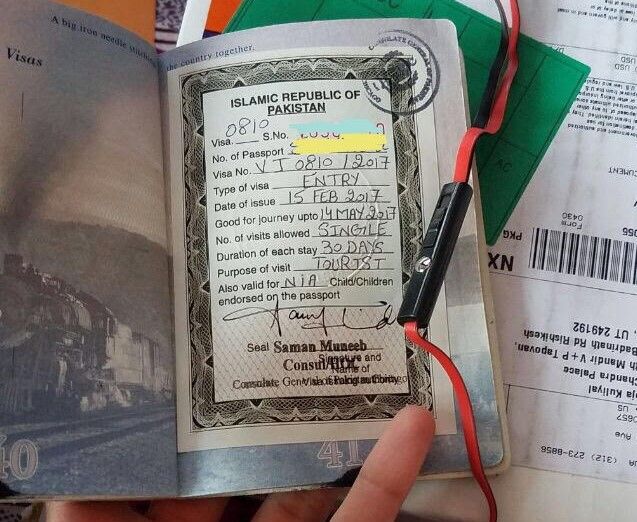

My first application for a Pakistani visa was scoffed at the embassy in Phnom Penh, where I had been working. I had prepared the documents to the exact specifications requested by the embassy, and I was assured over the phone that the process would be straightforward.

After a long wait, the consulate official finally arrived. I greeted him with the traditional As-salam Alaikum I’d used since I was a child, hoping our shared Islamic heritage might smooth over the process. He replied warmly enough and began reviewing my paperwork for a minute or two before he paused.