April 25, 2015, lives on in the nightmares of those who were on Mt. Everest that day, when a magnitude 7.8 earthquake rattled the Himalayas and ravaged the nation of Nepal. Among those to experience the single deadliest day in the mountain’s living history was mountaineer and author Jim Davidson.

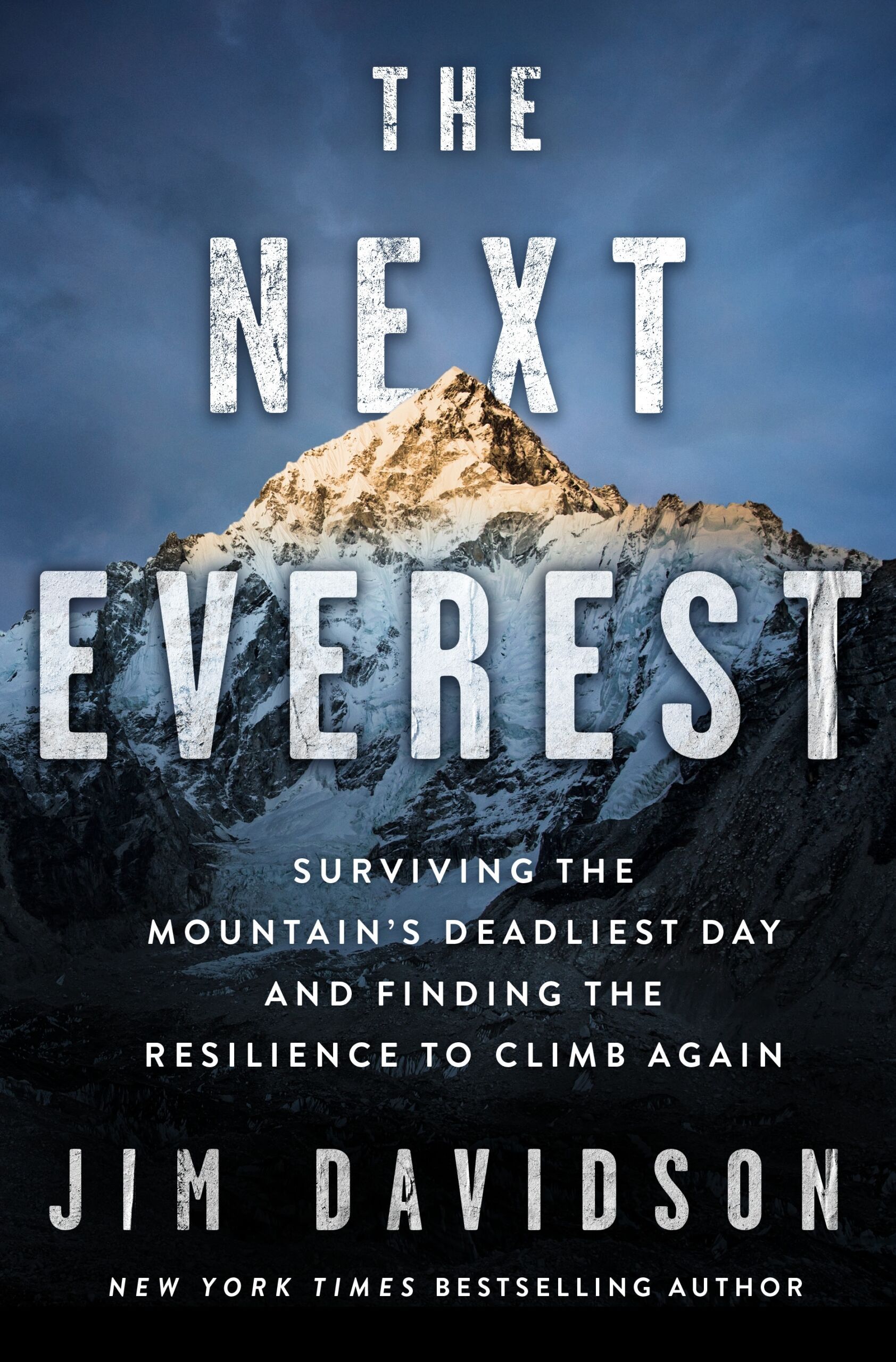

In a new book, Davidson looks back at the terrifying events that he and a team of climbers with International Mountain Guides lived through on their ascent to the world’s tallest peak. The Next Everest: Surviving The Mountain’s Deadliest Day and Finding The Resilience To Climb Again, out now from St. Martin’s Press, details the harrowing events that transpired and his drive to get back to Nepal and stand on the peak he’s dreamed of for more than three decades.