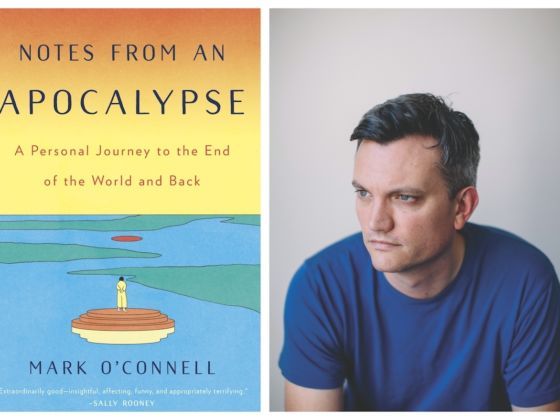

Mark O’Connell is obsessed with the end of the world. He can’t stop thinking about the ways that humans fantasize about the end times — with their bunkers, and zombie movies, and tours of places that have already been touched by their own kind apocalypse. So he decided to go looking for it — the end of the world, that is. As O’Connell finds out in his new book, Notes from the Apocalypse, he’s not the only one preparing for the worst.

Why There's Still Hope for Humanity, According to the Author of 'Notes From the Apocalypse'

On Youtube, O’Connell dives head first into the world of self-professed doomsday preppers — a group of mostly white men who actively prepare for the collapse of civilization by transforming themselves into survivalists. In Los Angeles, O’Connell attends a conference focused on how to build a human settlement on Mars. He even tours luxury bunkers in South Dakota.

O’Connell seems inclined to chase down apocalypse obsessives who prove that humanity might be doomed after all, but his journey only reinforced that he wanted to find the good in the world — rather than just highlighting the bad.

“I was trying to break through the hard carapace of cynicism that had grown around me,” O’Connell tells me. “I am a little cynical, but I don’t think it’s a particularly useful tool to bring to writing. What’s interesting is the effort to get beyond it.”

Getting beyond cynicism turned out to be a tricky proposition. O’Connell says he did “a lot of flinching,” while writing the book — that indeed, “the whole book, in a way, is an extended exploration of what it’s like to be constantly flinching, while also trying not to look away.” But to understand how humanity responds to panic and chaos, O’Connell forced himself to stare down every worst-case scenario for the end times (which included a trip to Chernobyl that he “wouldn’t recommend as an experience”). And what he found should be reassuring, especially since the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“People — whole populations — are acting out of communal self-interest in a way that I haven’t seen in my lifetime. This virus is doing a lot of damage to a lot of good things, but it’s also causing, I think, irreparable damage to the idea of humans as isolated individuals pursuing their own self-interest. And that’s something that gives me hope, albeit tentatively, for the future,” he says.

To some readers, the pandemic might have ushered in the apocalypse O’Connell is searching for, but he’s not entirely convinced. Some humans might wring their hands about our chance of survival if the planet decides we’re no longer welcome while others would rightfully argue that — depending on their religion, the color of their skin, or where they grew up — the apocalypse has already come and gone. As it turns out, the end of the world is relative.

“I’m trying to write about apocalyptic anxiety while keeping in mind that it’s both always the end of the world, and never actually the end of the world,” says O’Connell. “When privileged people in the privileged countries of the world talk about ‘the apocalypse,’ we’re mostly talking about having to live in a way that a large part of the world already lives.”

That sentiment might help some people appreciate how good they’ve got it in a time when people are losing entire livelihoods and loved ones, but it doesn’t change the fact that while we’re stuck inside, many of us are contemplating how different the world will look when businesses and workspaces open up again. Will the world we enter be one we even recognize? And how can we support the people who lost jobs and family members in this new world order?

There are no clear-cut answers. Yet watching as communities come together to support their neighbors who face food and housing insecurity, whether that means cooking meals for each other or launching funding efforts for struggling small businesses, might bolster your spirits. In between dire glimpses of people content to hide away in their concrete bomb shelters or shoot themselves to Mars as society crumbles, O’Connell sees even more people stepping up — proof that humans are still capable of the acts of decency required to ensure that we survive the apocalypse.

“One of the major strands running through the book has to do with the belief that civilization is extremely fragile, and that people will inevitably revert to savagery given a serious enough disaster,” says O’Connell. “Something that’s been very striking to me is that people are overwhelmingly behaving with great restraint and respect, and with a sense of a shared purpose. Community, in other words, is holding strong in a way that so many of the apocalyptic obsessives in my book would not have predicted.”

So that’s one cause for celebration in a time of unprecedented anxiety, grief, and despair. It’s tempting, of course, to give in to feelings of total despondency — especially if you’re someone who was laid off the job that supported your family, or you spent your life working toward opening a small business that is now floundering. There are good reasons for the bleak outlook that seems to consume all our days.

Yet O’Connell’s book, which does highlight some of the people who think the worst is yet to come, is, at its heart, an homage to what our world still has to offer. There’s no reason to give up on this planet or its people, to abandon it when times get tough. There is still so much of it to see, to explore, to celebrate.

“I want my writing to communicate, amid all the darkness and uncertainty and injustice, that the world is an interesting place,” he says. “The world is a beautiful, fascinating place, full of strange and wonderful things, and to ignore that in favour of obsessing about the apocalypse is to be complicit with disaster.”