During the first wave of the pandemic, photographer Brian Bowen Smith parked his car in the middle of the street in Times Square and spent 15 minutes taking photos. Anyone who has been to, or even seen an image of, New York’s biggest tourist attraction knows that what Smith did would have been unthinkable prior to March of 2020.

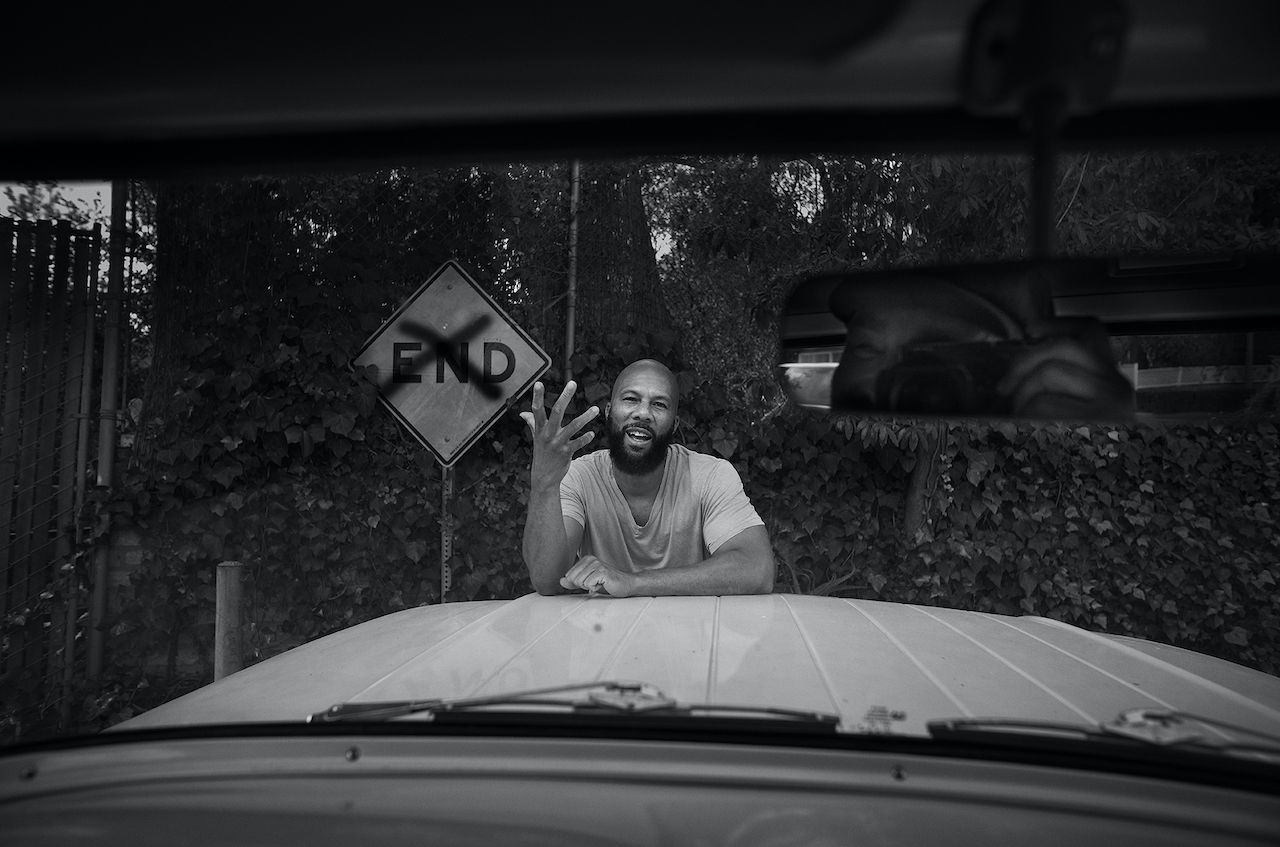

Smith set out from his home in Los Angeles at the start of the pandemic with the goal of capturing this moment in history. He drove from coast to coast in a 1958 Ford F100, stopping in small towns and major cities and photographing people and places along the way with his Leica M10 Monochrom. He counted Reese Witherspoon and Common among his subjects, but also dairy farmers and people just trying to get by.