Murmansk, Russia was the northernmost point on the map I had ever been to. Starting at the 69th parallel north, I was about to travel along the invisible line that separates Europe from Asia to reach lower Iran, partly to experience the incomparable strangeness of the New East again, and partly to invest the two months at my disposal in an itinerary I hadn’t heard anyone following before.

Traveling Overland From the Very Top of Russia to the Bottom of Iran

I had flown into Saint Petersburg from Amsterdam, and had caught a 25-hour train to Murmansk, the largest city in the Arctic Circle. Waiting for me at the railway station was not my flaky Couchsurfing host, but two police officers and an interpreter. It was the middle of the night in Murmansk, but the sun was still floating in its mid-afternoon position — summer at this latitude means total absence of darkness. “What are you doing here? There are no matches in Murmansk,” the police asked while checking my passport. It was the final days of the 2018 FIFA World Cup and while thousands of visitors had flown into Russia to support their national teams, I was not one of them. “Just…visiting?” I answered.

I was let go with a “Welcome” into what appeared to be a ghost Soviet city, with wide avenues devoid of traffic and only a McDonalds — the northernmost McDonalds in the world — showing some signs of life. Walking along Leninskaya as the city fell asleep under a bright sky felt like an intrusion into an alien environment.

Just three hours away from the Norwegian border, Murmansk is a city of iron and concrete. Its large port, upon which the city’s economy relies, remains ice-free all year round thanks to the North Atlantic current, and hosts the museum ship Lenin, the first atomic-powered vessel, together with the largest fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers. Remnants of the USSR are not found only in the port: surrounding a Hollywood-style sign with the city’s name, gray apartment blocks encircle the town center under the watch of soldier Alyosha, a gigantic monument to the memory of the fighters of WWII.

The UNESCO-listed Kizhi Island was the first stop on my slow descent toward the Caucasus. From Petrozavodsk, a 90-minute hydrofoil trip on Lake Onega got me to the open-air museum of Kizhi, where an incredible collection of centuries-old wooden houses and churches stand, away from the busy city. The blissful escape, however, was soon over: Moscow and its twelve million inhabitants were next on my itinerary.

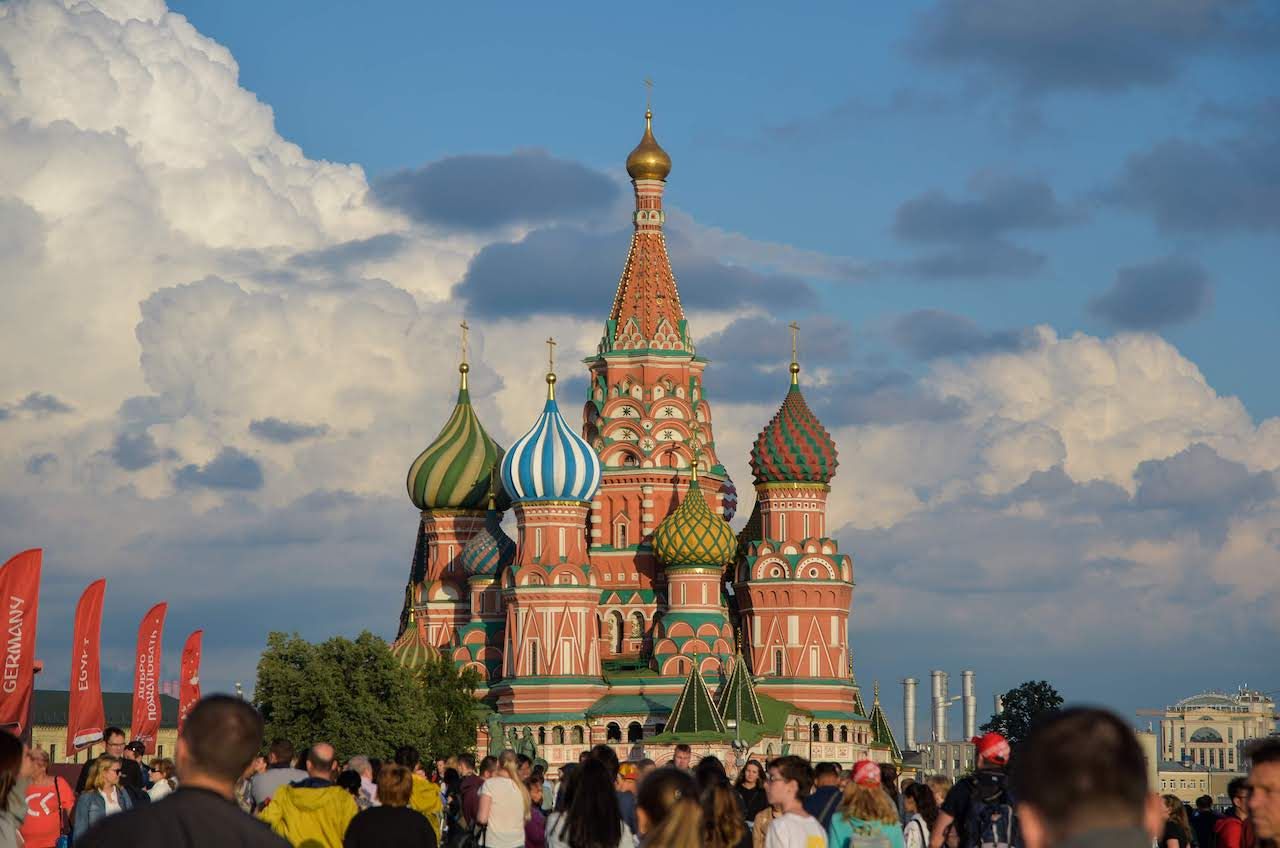

My first encoutner with the Russian capital was a stoned oddball who welcomed me in my hostel room by blowing his nose on the sheets. I guess a bit of care in picking where I sleep would have helped, but there I was, among Stalinist towers rising high on the skyline, fast-moving traffic on uncrossable avenues, and a mix of people running in every direction.

By the time I reached Volgograd (19 days into my trip), I had spent about 85 hours on trains, mostly in silence given that my language skills didn’t go much further than “Sorry, I don’t speak Russian.” From Moscow, a four-day detour had taken me to Kazan, famous for its UNESCO-listed, whitewashed Kremlin, but it was in the city once known as Stalingrad that Russia, as I had it pictured in my mind, came alive. Far from any tourist route, the industrial center of Volgograd is a city of records: it overlooks the longest river in Europe, the Volga; it hosts The Motherland Calls, the tallest statue of a woman in the world; and the tallest Lenin statue on the planet — not easy, given the sheer number of monuments dedicated to the Communist leader that are still standing.

In Volgograd, I abandoned rail in favor of asphalt until my not-yet-clear final destination. A marshrutka (minibus) drove me through the arid steppe into the Buddhist province of Kalmykia, and from there I reached the border city of Vladikavkaz to leave Russia behind after almost a month. Across the Greater Caucasus Mountains was Georgia, with its khachapuri (cheese bread), khinkali (dumplings), and sweet wine. Having been in Georgia before, I spent a short time in the country, just enough to discover Stalin’s secret printing house in Tbilisi and figure out the rest of my itinerary.

Thanks to new visa regulations, entering Azerbaijan is fairly simple today, unless you have previously visited the contested region of Nagorno-Karabakh. I traveled along the coastline via Baku, the capital, and down to Lankaran, the last major city before the Iranian border.

Lankaran is considered a “resort city” in Azerbaijan and, while I am no expert when it comes to resorts, this is not what I was expecting. After a busy seven-hour bus ride from Baku that involved a lot of exhaust smoke, a two-hour wait on the highway, and a rescue bus, I arrived in Lankaran. I quickly discovered that my hostel wasn’t really a hostel, but a construction site still lacking paintwork, hot water, and internet. The owner, a former KGB officer named Qeni, was prepared to mitigate any form of disappointment with an endless supply of vodka.

Since I was clearly unable to find a decent place to stay on my own, I decided that in Iran I would let fate decide where I should sleep. The day before crossing the border I put a message on Couchsurfing saying, “I will be in Rasht tomorrow, anyone able to host?” The famous Iranian hospitality is infallible — when I connected to Wi-Fi the next day, I had received 17 messages. I traveled most of the following three weeks by letting generous strangers influence my itinerary.

I met my first host, Motti, a 30-year-old architect, in front of a cafe. Her parents were gone for the weekend and she thought it would be a good idea to invite a guest over. I spent the next days touring Gilan province with Motti and her friends, visiting the 800-year-old city of Masouleh in the lush hills above Rasht and the villages along the coast. I then moved south to Kashan, but it was just a brief stop. After 24 hours I had received an invitation to join a road trip along the Caspian Coast. I explored Ramsar, Chalus, Tonekabon, and other villages I would never have seen had I not let kind strangers decide my journey.

Two women who had been reading my posts online offered me a ride to Hamedan, so it became my next destination. In Hamedan, Qasem and his family welcomed me into their house and through him, I ended up in Lalejin, the pottery capital of Iran. I found myself in an artisan’s workshop celebrating a birthday with a bottle of Grey Goose that had been smuggled in from Iraq, before being gifted with the ideal souvenir to carry around in a worn-out backpack: a set of ceramic pots. I visited the vast Alisadr caves, the world’s largest underground water hall, before moving on to Kermanshah. Here I was introduced to the ancient ritual sport known as zurkhaneh, an activity still widely practiced in clubs around the country which blends dance, weight lifting, and juggling.

I finished my journey by getting a bus to Yazd, one of the most picturesque cities I’ve ever seen, and then Kerman. I spent the final week of my journey between remains of the Zoroastrian tradition, labyrinthine alleyways, and covered bazaars offering refuge from the 113-degree heat. Then, as my second month on the road was coming to a close, it was time to get back to Tehran, conclude this 5,000-mile trip, and catch a flight back home with a backpack full of tea, nabot (rock candy), and odd gifts collected along the way.

I often wonder how far I would have gone if, instead, I kept hitching rides without an end goal in mind — pretty far, I’m sure. But, as cliché as it sounds, the destination doesn’t matter so much as the journey, especially when you’re traveling overland.