Some dreams are made of this, but most others are made of heavy duty double-sided tape. Clingy and persistent, they stick around, refusing to budge regardless of the circumstances threatening their fruition, or how much effort you put into willing them away. There’s no use trying to peel them off in favour of something simpler, easier, or more conventional. And for those left untended? They often turn to torment.

Beyond Wanderlust -- I Quit My Job to Travel Indefinitely, but I Did It to Survive

Such is the nature of my wanderlust and the ways in which it consumes me.

In spite of an identity shrouded in otherness and stunted by restriction, I too desire travel for some of the reasons commonly romanticised in Western culture. I too want pleasure and experience through personal contact with the sights, sounds, flavours and traditions of foreign destinations. But somewhere, between the international refugee crisis and characteristically North American lifestyles blessed with the luxury of choice, you’ll find me, not on a beach in the Seychelles, but facing a world-map-covered concrete wall, in the house my only remaining parent kicked me out of five months ago.

Here, in this precarious position, I’m reading an article about a broke college student who saved $11,000 in eight months, $8,000 of which she earned in a single summer, for a postgrad trip to Southeast Asia.

I’m trying, really trying, to buy what she’s selling. But I can’t even make a down payment because my annual, full-time salary was significantly less than what she, a broke college student, saved with only a summer internship and a strict financial diet. Instead, all I can muster is a deep sigh and an even deeper contemplation of travel as not just pleasurable escapism, but wilful displacement.

Travel, for myself and many other young, Caribbean people, isn’t just about satisfying a super sticky sense of wanderlust. It’s a desperate draw on a complex survival tactic that’s been stitched into the fabric of our cultural DNA.

One practice of creative people who hate their jobs is wearing headphones all day and listening to whatever as loudly as possible to disconnect and zone out. Or, specifically, it was the general practice of me — the office downer, who barely spoke to anyone and participated in nothing.

I showed up to work most days with nothing more in mind than doing my job while avoiding as best as I could every water cooler quip, work email sent after 4:01 and, most importantly, conversations about current events.

Oh, how I detested any utterance in that office about anything particularly newsworthy.

If anyone dared mention African Americans, police brutality, racism, feminism, PNP, JLP, di ting pon Facebook or homosexuality, I’d be immediately hurled into a dimension that was very much like earth* except the only country was Jamaica, and the only inhabitants were myself and all my coworkers unanimously asserting the most absurd opinions, over and over, in their most obnoxious voices.

Hell*.

So, try to imagine my confusion when, earlier this year, I overheard a conversation that actually piqued my interest. It was a Friday, payday, and we hadn’t been paid yet. Catherine, a straightforward woman who’s been travelling the world since before I was conceived, was panicking because she had no food at home, barely enough gas to get her through the weekend, bills to pay and no rainy day funds to bail her out. A curious coworker, Canton, asked how she managed to be so broke yet so well travelled. Catherine, who was saving for an upcoming trip to The Netherlands, responded plainly and without hesitation:

“I pay for my trips with credit cards. And loans from Credit Union.”

Canton pushed through his own laughter to rise above the clamouring input of our coworkers. “So, wait,” he said.

“You have credit card and you can’t buy food?”

“Ah who dat? Who have credit card and cyah pay dem rent?”

“She nuh mussi mek di bill dem pile up, man. Don’t ah dat yuh do, Cat? ”

“Smaddy can ah guh Europe every year and can’t even buy tin mackerel when dem paycheque late?”

Laughter boomed as if from the cavernous chest of a single beast.

A distant voice yelled, “Leave my friend alone!” Reasonably stating, “Your life isn’t any of their business.”

But Catherine, a woman of tremendous grit, was unfazed by the prospect of divulging the type of intimate details most people hesitate to talk about with their own conscience. She powered through.

“No, no, I have more than one credit card. I use one to pay for my trip and then another one to pay it off.”

“So wait — ”

“And sometimes I take out loans and just use that.”

“So how you pay it back?”

“What?”

“The credit card you use fi pay off your other credit card bill dem.”

“Oh, well. I, just. I don’t know — ” She belched, the office protested, then through a chuckle, she said:

“I just always in some whole heapa debt.”

Laughter and derision ensued. Which, naturally, didn’t deter Cat from chiming in occasionally to defend herself. When Canton asked why she didn’t pursue a side hustle to make a little change, she expressed complete disinterest. She didn’t care what anyone thought about her financial situation and seemed either oblivious to or unbothered by it. Travel, she explained, was her main priority. It’s what made her happiest in her simple, solitary life and so she did whatever she could to make it happen, as often and as much as possible.

This warmed my heart as it skipped a beat, because Catherine wasn’t a woman I’d thought I had anything in common with. She is tall and fair with an addiction to sugary snacks and caffeinated soda, thinks locs are dirty but can’t find a thing on her work desk, is old enough to be a young grandmother, but speaks, more often than not, with the limited purview of a child with average intelligence. Yet, we both desire travel. So much so, we prioritise it.

On my way home that day, to my room and my parents, I imagined Catherine’s life as a sort of worst-case-scenario foreshadowing of my future. She’d been working at the company for over a decade without a pay raise or the benefits warranted by full-time employment. But there she stayed, hand to mouth, month after month, working for menial pay for no other reason than to afford a dream that left her finances in ruin.

And, we had shit in common.

Generally speaking, my situation leading up to that point was not the worst. Three years prior I’d graduated with a communications degree that my parents had already paid for, and with the design skills I’d acquired as an undergrad, I managed to pursue a mostly miserable postgrad life as a freelance web designer. I made just enough money to trick myself into believing I was independent, but I wasn’t. I clothed myself and paid for a lot of my own shit but I was still, though significantly lighter, a financial burden to my parents. I wanted desperately to stand without being propped up by their bank accounts. I wanted to show them, in addition to the fervour with which I consistently told them, that I was grateful for all they’d sacrificed to give me a debt free shot at adult life.

And so, to the horror of all my hopes and dreams, I got lucky and landed my first real 9 to 5 where I promptly drew up my very own swivel chair in my very own corporate grey-coloured cubicle, just down the hall from Catherine’s.

It wasn’t what I wanted to do, but it was the best I could hope for and I’d gotten it. Despite having to show up at a specific time to a specific building where I’d go to a specific floor and sit in a specific corner of a specific room in front of a specific computer connected to a specific Internet connection to do work I could literally get done on any computer with Photoshop and wifi, I was happy to be lead web designer (see: only web designer) at a regional university.

It was a good job by Western standards and a very good job by Jamaica’s. But I earned a net salary that was thousands of dollars less than what a broke college student saved in eight months. That is, for your reference, $11,000.

This is unsurprising when you consider that the antiquated United States Federal Minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, or $13,926.38 per year, after Social Security and Medicare taxes, is barely a living wage for many single, full-time American employees. But, it’s still an incredible (see: laugh-cryable) 600% more than Jamaica’s minimum wage of $1.17 USD per hour, calculated at a rate of 118 US dollars to 1 Jamaican dollar — a value that, literally, depreciated as I wrote this.

All the same, in my second year working full-time, I took with me the false sense of security provided by regular paycheques and leapt into the decision to rent my own, uncomfortable apartment.

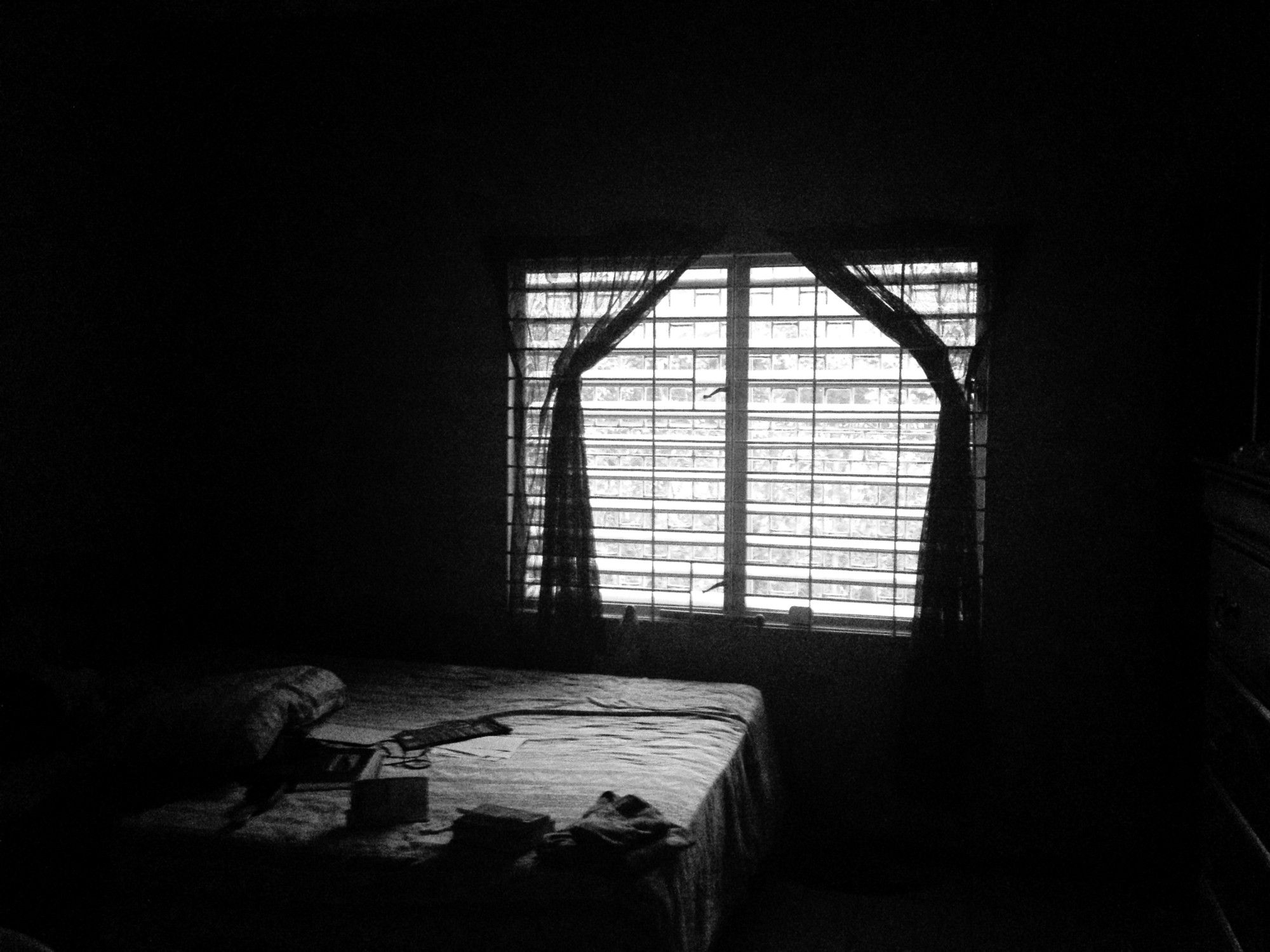

It was bad, but it was mine. It was a mistake, but I wanted to make my parents proud, be independent and finally have a space in my whole entire life where I could be openly queer without losing my mind or basic needs.

I took with me all the furniture that was in my room: a bed, a desk and a bedside table. I couldn’t afford to purchase large appliances cash, so I took them out on a Hire Purchase contract which, aha, created my first source of, ahahaha, debt.

For an entire year, I never invited anyone to my eyesore of a apartment. In fact, what I refer to as an apartment was actually just a tenement yard partitioned three ways, with two doors being all that separated me from neighbours who had little qualms with rats and roaches.

To make matters even more befitting of the super dramatic tragedy I’ve probably been painting, my mental and physical health plummeted. I was eating horribly for comfort and economy and my body responded with vengeance. First, I developed a scaly, white rash that went up and down my chest, abdomen and back. Fortunately, it didn’t itch or cause me any physical pain, so I tried, and failed, to diagnose it myself because I couldn’t afford a doctor and didn’t have the benefit of health insurance from work yet.

With all of that I developed a dependency on sleeping pills, suffered more frequent migraines than usual, and was completely useless in social situations because I was so anxious and depressed all the time.

And still, still! I had the sticky desire to travel. But I also had the despairing realisation that if I kept my good job and independence I would never be able to afford it. Not if I wanted to live in a nicer neighbourhood and apartment, own a car or pay mortgage someday. Not if I wanted to eat well and maintain my physical and emotional wellbeing.

Maybe you’re thinking, “Gurrl, travel is not essential. You could’ve just accepted that you’d have to do without it and live more conventional life.” Well, gurrl, what does a conventional life look like when your very good job is dead-end and can’t support it? What does a conventional life look like when the idea of having a proper savings account is like a full on, completely unattainable wet dream? What does a conventional life look like in a country where simply being — ideas, desires, orientation and all — is an affront to the dominant culture?

It wasn’t impossible to get a side hustle, buy a car, and mortgage a house. But what would that journey look like? How would my debt compare to my liquid assets? In what new and masterful ways would my suffocated dreams sabotage my sleep?

Do you see? I couldn’t afford to be independent, live frugally and travel, nor could I afford to say fuck travel and live a conventional life that was comfortable or fulfilling. I really couldn’t win. And with that realisation my desire for travel shifted from an overwhelming sense of wanderlust to something more akin to what a wild bird must feel a moment after it’s just been caged.

Jamaican millennials grew up in a culture where travel was done out of necessity first, and for pleasure second. We grew up in homes where a parent’s presence might’ve been felt most strongly through the arrival of a barrel at the wharf, hazy collect calls or standing in line with a grandma or aunty, waiting anxiously for a MoneyGram cheque.

By the time we get to high school we’re primed to begin anxiously planning our own escape if no one’s already planning it for us. We’re thinking about a place that’ll be fun for four years, and we’re thinking about scholarships, and we’re thinking about taking SATs and we’re thinking about taking CSECs, and we’re thinking about “being black in X” where X is the geographical location of the universities in question, and we’re thinking about a major that’ll bring us career fulfilment for the rest of our lives but also get us hired in a city that’ll hopefully be hospitable to our kind.

If we’re lucky, we take all the standardised tests available to humanity, score big and receive scholarships, get the visa, buy a plane ticket, and jet off to what we hope will be a shot at making something good out of life. As for those of us who remain, we set out on futile job hunts, pursue degrees, or harbour sticky, often unconventional dreams like travelling the world indefinitely or being successful, and content.

For many American millennials, the prospects aren’t hugely different. But the outcomes certainly are. An American might take months to land a job, and then that job might be at Wendy’s, but then it’ll likely earn them more than many Jamaicans who leave school and are lucky enough to get full-time employment in a position that require’s the qualifications of a first degree.

And surely, not all Americans are wrestling with themselves about choosing between their dream job, or any job, and a life of travel. But, for those who are, the travel they think of almost always puts them on white sand beaches in third world countries, while the type of travel a Jamaican might contemplate will likely put them in a long, snaking line down a heated sidewalk where they’ll wait to be enveloped by the temperate air of the US Embassy — the thought of possibly being denied a visa weighing heavier on their mind than a backpacker’s luggage on her spine.

For us, options often feel like ultimatums. My options were keeping my very good job or finding a way to combine my desire for travel with my need for a better life. For Tamara, a friend of my mother’s and a trained Nurse Anaesthetist, it was a choice between being at the top of her career but having to deal with the stress of working for a government that desperately needs but can’t afford her, or migrating to Canada where they’re equally desperate for her skills but are willing and able to pay her a living wage.

I mean, Tammy doesn’t have unconventional, double-sided adhesive dreams. She has a growing daughter and a young son who battles Sickle Cell Anaemia, and all she really dreams of is a place where she and her family will not just barely get by, but flourish.

One day, not long ago, I called her up to ask her advice on pursuing a career in Nutrition.

I said, “Is that an area with decent job prospect in Jamaica? Do you think I could live decently here if I got a second degree in something like that?”

She laughed. Then, she told me a story about a friend she had who’d graduated from nursing school and was unable to find any local job in nursing for two whole years.

“And look how we always want nurses, eh?” She sighed. “Right now I’m overworked cause the ward so understaffed. And is not likkle nurses I know who still can’t find jobs.”

“But!” She brightened, “if you really want to do the nutrition, dietician thing, you should definitely try. I just wouldn’t recommend you do it out here. I know a dietician and I’ll ask her for you, but I’d say go America or Canada. More likely Canada, to be safe. And when it comes to work, you’re almost guaranteed to get a job. It’s going to be expensive, but trust me, if you can — try do it over there.”

The rubber washer in my shower tap broke and made me late for my last day of work. I got to the campus around 12:30, returned my I.D. and health cards to HR, then walked leisurely over to the building that housed my cold, grey desk.

I’d never been happier to sit at that desk. Knowing I was seeing it for the last time transported me to a carefree, spirited place and I embraced it as a welcome departure from the guilt and anxiety I’ve been harbouring about leaving my eight-year-old brother behind and adding to a theme of loss that’s so far pervaded his tiny little life.

I allowed myself the moment of happiness. And Catherine allowed herself a first time visit to my desk to offer friendly advice and candid questions about my travel plans.

“Can you teach English in Europe?” is mostly what she wanted to know.

I told her I had no interest in visiting Europe, for the most part, and would likely stick to South and Latin America for a while.

“But I don’t really know what I’m doing after Mexico,” I said. “But I’m almost sure it’s nothing in Europe.”

Her mouth, a crumpled line of confusion, uttered a feeble, “Why?”

“I’m not interested.”

“But Europe,” she insisted “is so nice. I love Europe. You should go.”

“And you should maybe go to a country in Africa or South America.”

“Uhg. Well, I’ve been to Mexico. Long, long time ago in high school, for a school trip. The people were so friendly there, and the men were so nice to us! But oh my, it don’t make no sense to marry none of them!” She hugged her belly and guffawed. “You need to find a man, Rushel! And upgrade your passport.”

I smiled, unsurprised. I might’ve nodded encouragingly, because she did carry on.

“Our Jamaican passport is so worthless. I think you should give it a try, you’ll like it.”

“What? A man?”

She squealed. “That too! But you should go to Europe. Go to Belgium, or Holland or Spain.”

With her head tilted slightly, eyes glistening under humming fluorescents, Catherine regaled me with as many travel stories as she could fit into ten minutes. Racist couch surfers, being yelled at for walking in a bike riding path in Holland, shopping in Spain, and long distance love connections that never amounted to much. I was transfixed, and then she said,

“Our Jamaican passport is rubbish. You’re young, you can find a man in Europe quick. You still have time.”

“And no Schengen visa.”

“Oh, well…”

“Is it hard to get?”

Cat explained that she’d applied for the Schengen visa every year since the first time she travelled to Europe, and each time she only received a single entry for the length of her stay.

“Plus they always ask for my parent’s UK passports. Sometimes I think that’s the only reason I get it.”

“Hmm.”

“But you’ve been to Canada, don’t? You could go there after you teach English then. Canadian men are nice.”

I envy the people who feel rooted in their professional aspirations of 9 to 5, mortgage on the two-car garage home in a quiet suburban area only a short drive from the city, neighbourhood watch and a couple private schools nearby — you know, that sorta thing. I envy them because there’re so many examples of that path. They have the failures and the successes lined out before them; carving that path is a matter of common sense, breaking some rules, following some other ones, doing what dad did and what aunt Dorothy failed to do.

For people like me, though, there are no rules to break or examples to follow. People like me don’t want to feel rooted in the conveniences of routine, taxed income and paid vacations. People like me have no desire to own a house; I want to call many places home. I want to use would be car payments to buy plane tickets. I want to explore passions on my own time, rather than report to work for 9.

People like me, I guess, are what people like dad and Dorothy call lazy, or confused, or wayward in their youth.

People like me eventually lose themselves amid picket fences and family dogs, waiting on someone like them to reveal the secret to being themselves.

I wrote that a very long time ago. I was probably around 18, and only two things have changed:

1. With very few exceptions, taxed income is inescapable. I know that now.

2. I definitely would like to own a house, but mostly because I want to rent it out to travellers on something like Airbnb someday.

I wasn’t kidding about dreams, ya’ll. They’re sticky as fuck and they will, you know, fuck you up. And so it’s easy to be swept up in the expression of a desire that hits close to home, until you realise that it has nothing to do with you. Advice about cutting out things like Starbucks have nothing to do with me, and saving $8000 while working a summer job has nothing to do with me.

But it’s the valid experiences of my millennial neighbours up north who grew up on the same TV shows as me, and visit the same websites as me, and want a lot of the same things as me, and so it’s easy to think that they speak for me, or people like me, when they don’t.

It’s important that there’s an adequate platform in the travel community for voices like yours and Catherine’s and Tamara’s and mine. For voices that aren’t white, or first world, or straight or exclusively from a point of view that benefits from the privileges afforded by identifying as any of those things.

“Stories matter. Many stories matter.” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie says on The Danger of a Single Story. “…When we reject the single story, when we realise that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise.”

Like is dangerous enough. And there is paradise to be had.

*All names have been changed.

This article originally appeared on Stories by Soujournie and is republished here with permission.