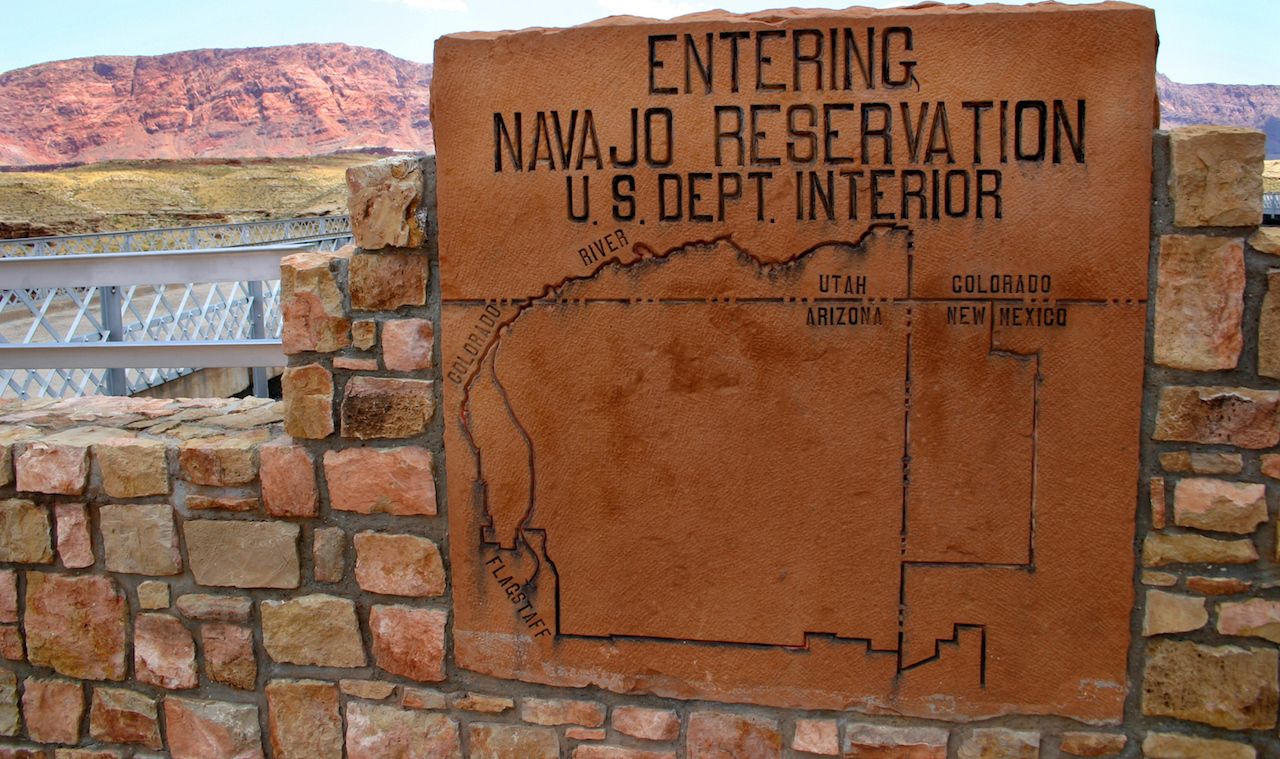

Experiencing a beautiful outdoor space is a surefire way to be convinced of its value and need for protection. Sometimes, as a responsible outdoors person, it’s more important to leave that magical space alone. The sacredness of ancestral lands to Native Americans is far more important than our desire to use it for recreation or exploit it for profit, especially when that land, or anywhere else, isn’t ours to begin with. Native American tribes occupy, operate, and live on vast stretches of open land across the United States. They revere their beautiful land. And if we choose to visit, it’s on us to not climb, hike, or float on restricted areas that look oh so tempting — because protecting their hallowed spaces is far more important than experiencing what is epic.

Before You Head Outdoors, Be Sure You’re Respecting Sacred Grounds

When planning to visit Native land, visit the tribe’s website first to confirm access

Photo: Galyna Andrushko/Shutterstock

In 1971, the American Alpine Club published a letter from Navajo Parks & Recreation Department’s Charles Damon to rock climbers, explaining the Navajo Nation’s ban on climbing on its land. The letter included the following:

“A practical and easily understandable reason is the nature of the rocks themselves, which cannot withstand unnecessary attrition to any degree. This has been argued by various would-be climbers, but the Tribe is making no exceptions.

“A second reason and one that admits of no argument is that the monoliths of the Navajo reservation are considered sacred places. To climb them is to profane them. Protests have been and still are being made by the Navajos about the unauthorized scaling of reservation rocks.”

Unfortunately, nearly 50 years later, illegal climbing on their sacred land is still an issue the Diné face.

That’s not to say there aren’t many beautiful spaces to legally recreate in the Navajo Nation. A quick look at the Navajo Nation website encourages visitors to check out places such as the Bisti Badlands, home to some of the best hiking and picturesque rock monoliths in the southwestern United States. Website forums and social media groups such as Diné (Navajo) Climbing & Outdoors are active to help visitors know what is legal to climb and what isn’t, and to give visitors a chance to support local outdoor communities.

The same is true of tribal lands across the country. Devil’s Tower National Monument, in northeastern Wyoming, is voluntarily closed to climbers each June for Native ceremonies. Climbers have an entire season to climb the tower, yet many — mostly local and regional climbers, according to a report from Wyoming Public Media — feel the need to proceed in June. In order to avoid trespassing on or disrespecting sacred land, local climbers could very easily climb elsewhere during the month of June.

To find out whether an area you wish to access is open to the public, check the official website for visitor information before you even put boots to trail. There you’ll find where to go and any permits needed for access, learn about what is off-limits, and familiarize yourself with any local rules, regulations, and customs that may be different from what you’re used to at home.

Support protests and campaigns championed by Native tribes, and for the right reasons

Photo: Diego G Diaz/Shutterstock

In December 2017, President Donald Trump announced his intention to slash the protected areas around the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments by more than two million acres. Trump’s announcement sparked immediate outrage in conservation circles, as well as among Native American tribes and public lands supporters. Petitions were circulated, protests held, and articles written by outdoor-centric publications, including Matador. While many activists and journalists acknowledged that the land surrounding Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante has long been sacred to six Native American tribes, this was often a footnote to what was seen as the more immediate problem: He’s cutting into our recreation space, bro!

This attitude is a major bummer, one I’ve admittedly been guilty of having. From the perspective of those who’ve stood as true stewards of the land for generations, it is also morally indefensible. While vitally important to economies across the West, and an incredible way to find meaning in one’s life, outdoor recreation is not the most important factor at stake in the vast majority of land conservation issues. Looking beyond even the threat to wildlife habitats and biodiversity, many sought-after stretches of land across the United States (and Canada) are sacred to Indigenous peoples who have held spiritual and cultural reverence over the area for thousands of years. In this case, Trump’s modification is another example of the US government breaking a contract and betraying Native Americans.

When championing a conservation-related cause, take the time to dig into what’s at stake to parties beyond yourself and those you know. Almost without fail, this will light your fire even more. It is totally possible to be a non-Native outdoor recreationist who also champions Native rights, cultures, and land. To do so, you simply need to value the traditions that predate you by thousands of years and are ever more important than your own desire to hike, bike, ski, climb, or float in a given area in order to do your part in upholding contracts and showing respect to what is considered sacred.

How to show your support

Photo: Autumn’s Memories/Shutterstock

Often, recreating on that land is a part of conservation, but rarely is it the ultimate justification. The truest form of conservation is to leave a place better than you found it. When visiting spots on tribal lands that outsiders are allowed to patronize, follow the principles of Leave No Trace.

But we can also go further.

The Native American Rights Fund works to protect the natural resources of Native lands. Supporting its work, including with a donation, helps the organization stand ground against private or public interests seeking to exploit their land for profit.

Recreating responsibly while respecting sacred grounds is easily accomplished with a bit of forethought and an ability to think beyond one’s own desire for adventurous conquest. As Director Damons said 49 years ago, “Come and visit us, look and photograph as much as you like; you will be welcome. But please respect our prohibitions and let us keep the wonderful Navajo reservation as beautiful as it is.”