Early in a 2016 episode of Parts Unknown, Anthony Bourdain talked to an Argentinian psychiatrist about depression. Later, outside the confines of the stereotypical psychiatry office with a drink in hand, Bourdain opened up further. “I’m not going to get a lot of sympathy from people, frankly. I have the best job in the world.”

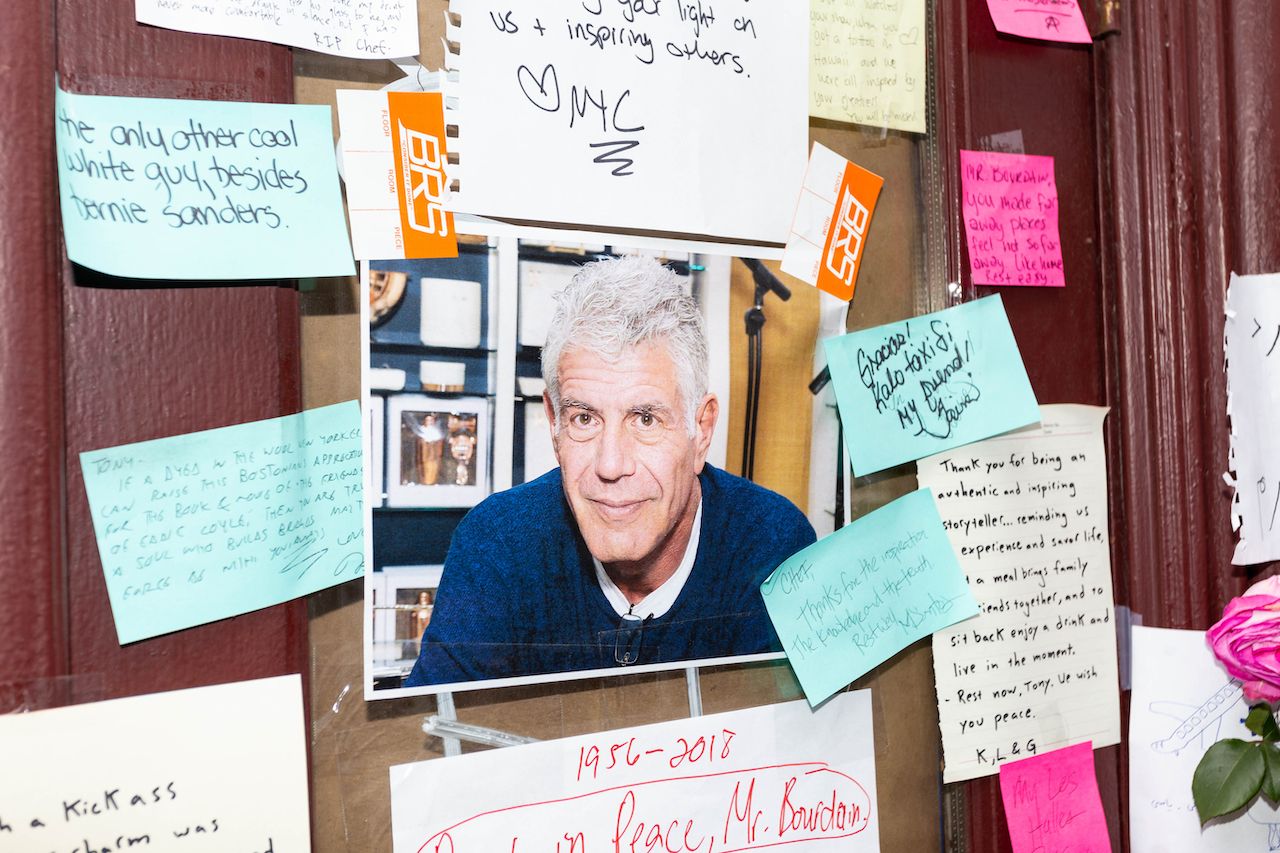

For the most part, he was wrong. People around the world — especially those in the restaurant industry and food media — collectively mourned when Bourdain committed suicide at the age of 61 in a hotel room in France while filming an episode of Parts Unknown on June 8, 2018. Yet three years after the Argentina episode aired, and more than a year after his suicide, there is one person with no sympathy for Bourdain: Dave Chappelle.