The most memorable things we come across when we travel often took a long, winding path to get to what they are today. This is Origin Story, a series that looks into the various influences that made the cultural touchstones and local quirks that we know today.

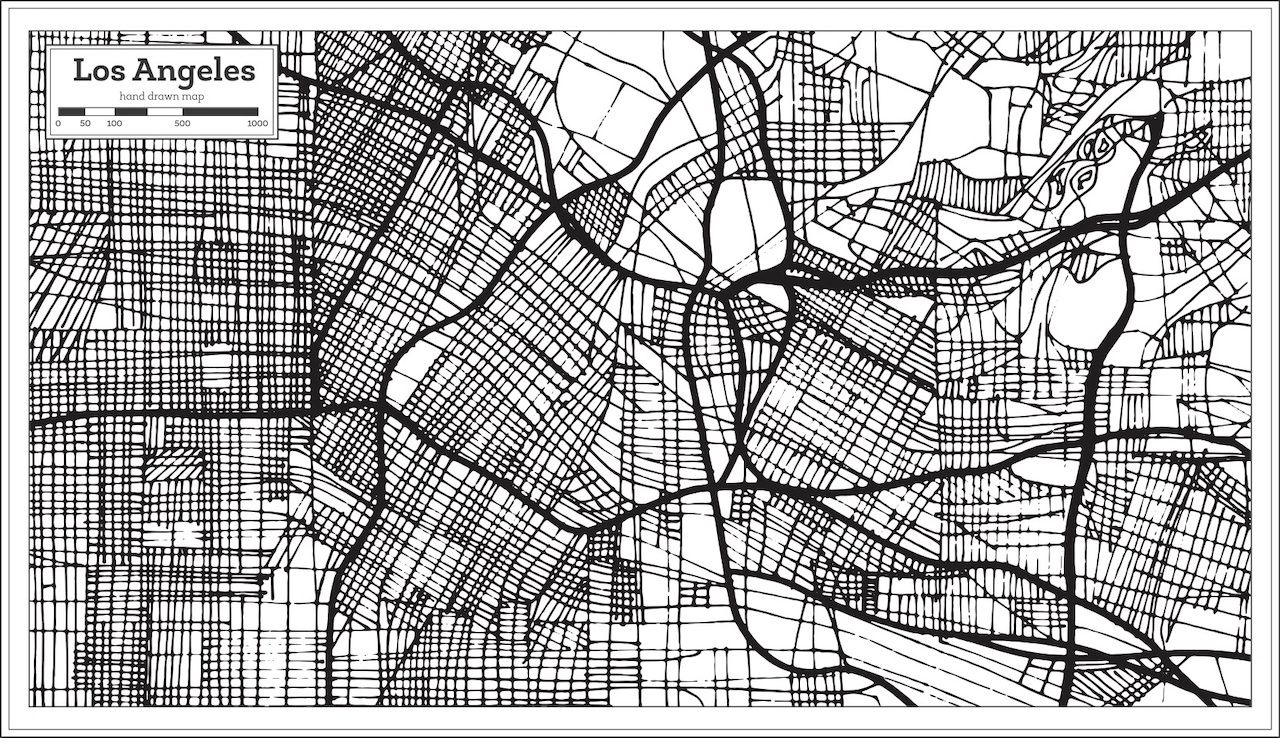

If you drive west from Downtown Los Angeles for long enough, you’ll be faced with a decision: Do you want to make a turn at a 45-degree angle or a turn at a 135-degree angle? The majority of the time that decision has to be made on Hoover Street, which delineates the northwest- and southwest-oriented streets of old Spanish LA and the north-, south-, east-, and west-oriented streets of modern LA.